Remember when we derived the cumulant as the solution to the pure th-order sine-wave problem? It sounded good at the time, I hope. But here I describe a curious special case where the interpretation of the cumulant as the pure component of a nonlinearly generated sine wave seems to break down.

Let’s consider a very simple cyclostationary signal, the baseband binary pulse-amplitude modulated (PAM) signal with rectangular pulses. This signal is a building block for a slightly more complicated and slightly more realistic signal, the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal. The latter builds on the binary PAM signal by adding a non-zero carrier offset frequency, a symbol-clock phase, and carrier phase. But overall the binary PAM signal is pretty much the same thing as a BPSK signal.

Here is a graphical representation of our binary PAM signal:

We know this signal has non-conjugate cycle frequencies equal to harmonics of and since it is real-valued, its conjugate cycle frequencies are identical to its non-conjugate cycle frequencies.

Let’s now take a look at the fourth-order parameters for the signal. First, consider the fourth-order temporal moment function with equal delays ,

The value of doesn’t matter here because

is real-valued, so we have

This moment function is trivially periodic, and so has a Fourier series expansion with a single coefficient. In other words, it is equivalent to a sine wave with zero frequency, unit amplitude, and zero phase. There is no symbol-rate fourth-order cyclic moment (no impure sine wave with non-zero frequency), nor any other non-trivial cyclic moment for the case of all delays being equal. Moreover, if we were to look at the second-order temporal moments with equal delays, they are also equal to one. So no non-trivial lower-order sine waves exist either.

What about when the delays are not all equal?

Let’s now consider the delay set .

Now we know that and

so that, once again,

Here, again, there are no impure sine waves with non-zero frequencies such as the symbol rate . What are the pure sine waves? Are they also absent?

Because the signal is real-valued, and we are considering only the fourth-order cumulant, our general moments-to-cumulants formula reduces to

From our previous analysis (for example (4)), we can replace several of these terms with unity:

so that our temporal cumulant becomes

or

The question then becomes: What is ? The periodic component of the lag product

is a square wave with period

and duty cycle of

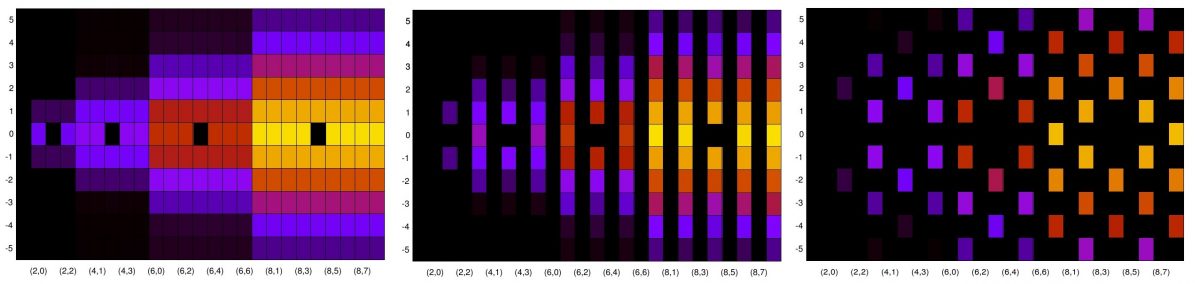

. We can see that graphically:

So the second-order moment is equal to that square wave (green lines), which can be expressed as a Fourier series. Let’s do that:

For ,

. For all other

,

We end up with

In particular, . This means that the cyclic cumulant

is not zero. That is, there is a pure fourth-order sine wave with frequency equal to the symbol rate

for the specified delay vector. But we already saw that there is no impure fourth-order sine wave with frequency equal to the symbol rate for that same delay vector.

Which is strange.

Let’s consider the moments and cumulants of a Gaussian signal for a moment. Recall that the th-order cumulants of a Gaussian random variable, set of jointly Gaussian random variables, or a Gaussian process (signal) are zero for

. So if we have a Gaussian signal

, we can write the following equation

where the outer sum is the sum over all the distinct partitions of the index set , each partition consists of

disjoint subsets of

denoted by

, the union of the

is the index set

,

, and

optional conjugations are included in

. (All that is review from this post.) Now consider

and for our Gaussian

we have

or

If we look at a single Fourier component of this time-varying moment (that is, look at a specific cyclic moment), we obtain

In other words, if you know all the lower-order cyclic moments with orders less than , you know the

th-order cyclic moment.

Now consider some even-order temporal moment function for our binary PAM signal , but also constrain the delay vector to be of the form

The moment function can be expressed in terms of the cumulant functions

Rearranging this equation yields an expression for the th-order cumulant

If we look at a Fourier component of this time-varying cumulant with , we get the cyclic cumulant,

In other words, if you know all the lower-order cyclic cumulants with orders less than , you know the

th-order cyclic cumulant.

In some sense, then, the binary rectangular-pulse PAM signal is the dual of the Gaussian signal. They play special roles in the interplay between cyclic moments and cyclic cumulants. Gaussian signals have minimum cyclic cumulants and cyclic moments with a sort of redundancy, whereas the binary PAM signals have minimum cyclic moments (under the constraint) and cyclic cumulants with a sort of redundancy.

I get the feeling I’m missing something fundamental here; some way to see these facts as aspects of a bigger idea. If you see anything, or have corrections or issues with the post, I encourage you to leave a comment below.