The CSP Blog has been getting lots of new visitors these past few months; welcome to all!

Following the CSP Blog

If you want to receive an email each time I publish a new post, look for the Follow Blog via Email widget on the right side of the Blog and enter an email address.

Helping the Signal Processing Community with the CSP Blog

I’ve received several comments and some email lately asking for code that reproduces some of the figures in the posts on the spectral correlation function, cyclic autocorrelation function, and cyclic cumulants. I don’t generally give out code that implements the estimators or even that just plots estimates.

This is mostly a self-help blog. I do spend time answering questions and helping debug readers’ code. I think writing the code yourself, though painful, is the way to learn CSP. And if you learn it well, then you can use it correctly, and I look good too.

New Rule for Getting My Help

I’m also going to use a new rule for providing help. I won’t give advice, answer technical questions, or help debug your code until after you post at least one comment to the blog. So if you start with sending me an email, then you’ll not get the help. This rule will help others benefit from your work.

Suggestions?

Since this is a “Blog Notes” post, I also invite you to leave any suggestions for blog improvement or new topics in the comments.

I’ve attempted writing some SCF code a few times (I don’t have thaaaat much spare time), but I’ve struggled testing it on real data. I assume because I’ve gotten the resolutions wrong. Is there a good rule of thumb for choosing these? I realise this is probably akin to choosing an FFT resolution where it depends on the data you expect and what features you wish to see. It would be cool if there was a way of determining ideal numbers.

What specific struggle did you experience? Incorrect detected cycle frequencies? No detected cycle frequencies?

I’ve not yet done a post on the various resolutions inherent in CSP (only the post on the resolution product), but here are a few notes. [Update 2019: Here is the post on temporal, spectral, and cycle-frequency resolutions in CSP.] If you process a block of data T seconds long, the temporal resolution of the estimate is T. The cycle resolution is 1/T. The frequency resolution depends on the estimator. For the FSM, it is the width of the smoothing function, for the TSM it is the reciprocal of the subblock length, and for the SSCA it is the number of channels (strips) times the sampling rate.

T is chosen by constraints on the collection or simulation, but if you have options, it should be chosen to accommodate the expected SINR for the signal of interest. That is, make T larger for lower SNR or lower SINR. I typically pick the frequency resolution to be around 1-5% of the sampling rate. For the SSCA, this means something like 32, 64, or 128 strips.

Since the choice of block length and frequency resolution always entails the spectral-analysis trade-off between estimate variability and estimate bias, I’m not sure there is an objective “ideal number(s)” to choose, even when you know a lot about the data. (Is there?)

It was usually just a mess, i.e. no visible/detected cycle frequencies. Just a sea of random noise. It would work when I used your basic examples.

Ideally, I would like to be able to detect some pool of known modulations, with some lower limit on SNR. Response time is measured in minutes, not sub-seconds, so there are plenty of samples available. There will also be some lower limit on detectable bandwidth. So these things will be known, and I know they will relate to the resolutions chosen.

What usually throws me is the resolution ratio >> 1. It’s very… vague. But I do understand why it is so.

Hello,

I’m currently implementing the FAM-Method for cyclic spectral estimation, the code is working, so for a BPSK Signal I’ll get a peak at the correct bitrate in alpha direction.

But my main issue is now, that between the PSD at alpha=0 and the peak for the bitrate the computed values for the SCF are almost as large as the second peak. This means that there is not a good distinction between the peak and nose between the PSD and the peak.

My question is now, is there a way to reduce this noise ?

Thanks for your help in advance, by the way, this is a really cool blog and helped me a lot.

Thanks for the comment Tuomas.

Well, I’m not sure that your FAM is correct, due to what you report. Since you are using BPSK as your input signal, you know exactly what the ideal spectral correlation function should look like, so you can attempt to determine the correctness of the FAM implementation by performing estimates with high measurement time-bandwidth product. The measurement time-bandwidth product is what I usually call the resolution product (see this post). It is the product of the data-record length and the spectral resolution. If you process samples and your FAM uses

samples and your FAM uses  channels, then the resolution product is

channels, then the resolution product is  . So make

. So make  large. As it gets larger, if the FAM is correct, all those false features between the bit rate and the PSD should get smaller and smaller.

large. As it gets larger, if the FAM is correct, all those false features between the bit rate and the PSD should get smaller and smaller.

When is fixed in some application, you may be able to increase the resolution product by decreasing

is fixed in some application, you may be able to increase the resolution product by decreasing  .

.

If you would like, you can send me your plots through email.

Does that help?

Hey,

First, many thanks for your answer. Actually I was able to solve the problem by myself. But anyway thanks for your answer.

The difference between your plots and mine were just the magnitude. As I was used to it from the normal PSD, I worked with a logarithmic magnitude. But after I changed to linear (as you wrote in your plots as well…) I was able to get the same results.

For the future project I’ll just use logarithmic magnitude, but the linear magnitude was extremely helpful for checking the algorithm for correctness.

Hey,

I am wondering that is this cyclostationary process suitable for analog modulation scheme such as AM, FM etc

Thanks for stopping by the CSP Blog, Yeni, and leaving a comment. Typical voice amplitude modulation (AM) signals, such as broadcast AM in the 540-1600 kHz band (USA) are cyclostationary signals. They possess a single conjugate cycle frequency equal to the doubled-carrier frequency, and no non-conjugate cycle frequencies. Typical voice frequency modulation (FM) signals, such as broadcast FM in the 88-108 MHz band do not possess useful cyclostationarity. That is, they may possess cycle frequencies, but they are not reliably present and the spectral correlation function is weak relative to the average power of the signal.

Hello,

I know this website through a paper related to ECG authentication, which analyzed the SCF of ECG signals. But though I have searched a lot from google about “cycle frequency”, I am still now confused about its definition.

This paper introduced ACF, the correlation between random variables corresponding to two time instants of the random signal. And it introduced how CAF could be extrapolated using Fourier series. But in this step, a new concept alpha, the cycle frequency was introduced, which makes me confused.

So the first question is, could you please give a definition of cycle frequency in SCF/CAF?

And also, because the equation referring to SCF given in this paper is for continuous signals. But while coding, the signal data appears with the form of points set with a sampling rate. How could this discrete points set be fed into SCF?

Thanks a ton!!

Thanks for stopping by the CSP Blog Shukai!

In CSP, a ‘cycle frequency’ is a Fourier-series frequency, where the Fourier series is applied to the autocorrelation function (your ‘ACF’ I believe). For cyclostationary signals, the ACF is a periodic function, and so is representable as a Fourier series. The Fourier frequencies are renamed ‘cycle frequencies’ and the Fourier coefficients are renamed ‘cyclic autocorrelation functions’ because they depend on the autocorrelation lag .

.

To get a more technical (mathematical) view of this, read the following posts in order:

Cyclic Autocorrelation

Spectral Correlation

Cyclic Temporal Cumulants

Conjugation Configurations

SO Symmetries

Estimation of Higher-Order Moments and Cumulants

Chad – Thanks to your blog (and Eric April’s paper) I was able to get a symbol rate estimator working using the SSCA. I have been testing it with various modulations and getting good results for PSK, QAM, FSK, CSS, etc. But I have noticed a few things that I would like to get your feedback on. I didn’t know which post was the best fit, so I defaulted to this one.

1 – OQPSK (aka SQPSK). For SRRC pulse shape, the base cyclic frequency is twice the symbol rate, which makes sense due to the I and Q symbols being offset. However, for rectangular pulses, the cyclic frequency is the symbol rate. This doesn’t make sense to me. Have you seen this?

2 – OFDM. It is my understanding that an individual OFDM symbol is not cyclostationary, since the data symbols are encoded via the amplitude and phase of the individual sub-carriers. If you consider multiple OFDM symbols, they are cyclostationary (the pilot sub-carriers certainly are). But if one can detect the OFDM symbols as energy pulses, the PRF is the cyclic frequency, so what is the point? Are Cyclostationary-based OFDM signal detectors only useful for weak signals (below the noise)?

I’d be grateful to hear your thoughts. TIA – Steve

Hey Steve! Thanks for checking out the CSP Blog and for the comment.

Great to hear this!

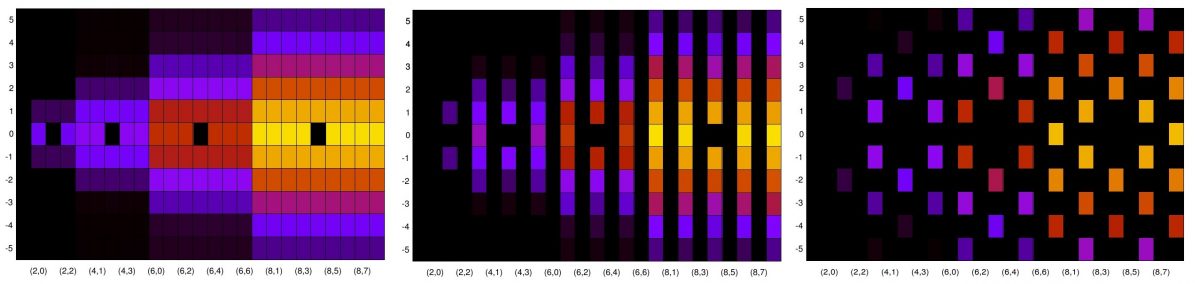

No, and I don’t think this is quite correct. For rectangular-pulse SQPSK, the smallest non-conjugate cycle frequency is twice the symbol rate. The features are the same as for rectangular-pulse BPSK, except every other one is missing. This leads to this measurement:

where the symbol rate is 0.1 and the carrier frequency offset is 0.05.

But for square-root raised-cosine SQPSK, there are no non-conjugate features (except for a cycle frequency of zero, of course). This is because the cycle-frequency pattern is the same as for rectangular-pulse SQPSK, but the bandwidth of the signal cannot support the larger non-conjugate cycle frequencies. That is, the symbol-rate feature is missing (by theory) and the next feature, twice the symbol rate, is larger than the occupied bandwidth, which is at its maximum for a rolloff parameter of one, and in that case it is equal to twice the symbol rate. So there aren’t any frequency components separated by twice the symbol rate that could be correlated. You end up with this measurement:

* * *

Agreed.

I don’t follow this if-then. I don’t think individual OFDM symbols are typically demarcated by a large quiet (no Tx) period. They are all sort of jammed together.

I think the cyclostationarity of most OFDM signals is weak. That is, the spectral coherence for the strongest features is small, even without noise present. If the pilots contain correlated sequence (for example, identical repeated sequences), then you can get fairly strong non-conjugate features for cycle frequencies equal to the pilot-subcarrier separations (see My Papers [16]). But overall, I don’t use CSP to detect and characterize OFDM signals–I use a non-CSP technique I invented a while back when I grew frustrated with the weak OFDM CS.

I figured out the strange rate features I was observing for rectangular pulse shapes. It was not a problem for OQPSK modulation. Rather it was related to the sample rate, or more specifically the number of samples per symbol. If the number of samples per symbol is an integer, all is well. However, if the sample rate is not an integer multiple of the symbol rate, then with a rectangular pulse shape I am effectively getting different symbol periods in the sampled data.

For example, if I sample at 5x, the alpha peaks are spaced at 1/5, and sampling at 6x forms peaks spaced at 1/6. However, if my sample rate is 5.5 times the symbol rate, some symbols have 5 samples and some symbols have 6 samples. This results in peaks at multiples of alpha = 1/11. Sampling at 5.25x gives peaks at 1/21 intervals.

This is not a problem for SRRC pulse shapes, as the phase transitions are smoothed out. In this case, sampling at 5.25 yields alpha peaks at +/- 1/5.25 as one would expect. I observed this phenomenon with rectangular BPSK and QPSK pulses also. So the obvious conclusion is that real-world signal data is easier to interpret than textbook signals! 😉

Progress!

Well, your signal generation method should work for all symbol rates, else you should be careful to never use rates that the software doesn’t support.

An easy way to get fractional symbol intervals is to generate a long signal with a large symbol interval, then decimate it or otherwise resample it.

But not for SQPSK I hope. As I claim above, there is no non-trivial non-conjugate cycle frequency for square-root raised-cosine SQPSK. The only valid non-conjugate cycle frequency is zero. Here I simulate SQPSK and QPSK signals with square-root raised-cosine pulses and a fractional symbol interval of 10.5 samples. So the symbol rate is 1/10.5 = 0.095238 and the carrier frequency offset is zero:

Rectangular-Pulse SQPSK:

Square-root raised-cosine (R = 0.5) SQPSK:

Square-root raised-cosine (R = 0.5) QPSK:

For rect-pulse SQPSK, the non-conjugate CFs are {2*k/10.5}, for square-root raised-cosine SQPSK, the non-conjugate CFs are {0}, and for square-root raised-cosine QPSK, the non-conjugate CFs are {0, 1/10.5}.

I think we are mostly in agreement. My signal generation code generates data points at specified sample times. This allows me to generate time-dilated data for changing path lengths due to relative motion between the receiver and transmitter (or reflector). So I don’t need to ever resample my data, which avoids creating strange artifacts due to filtering. It was a lot of work build signal models as functions of time, but I’m happy with my results.

So I generated the same 3 signals (SNR = 10 dB) and posted my results here: https://imgur.com/a/nOVBaa5

For the rectangular pulse SQPSK signal, I get the same highest peaks in the Non-Conj CS as you show at (-4,-2,0,2,4)/10.5. However, there are also many lower peaks, with the interval between all peaks being 1/21. Similarly for the Conj CS we have the same highest peaks, but there again are additional peaks at intervals of 1/21.

For the SRRC SQPSK signal, I see very weak peaks on the Non-Conj CS, at (-2,0,2)/10.5. The Conj CS has strong peaks at (-1,1)/10.5 which agrees with your example.

For the SRRC QPSK signal, the Non-Conj CS has peaks at (-1,0,1)/10.5, and the Conj CS has no peaks, both of which agree with your example.

So I’m going to stand by my assertion that rectangular pulses with non-integer over-sampling rates will lead to weak features at subharmonic cycle frequencies. This just makes intuitive sense to me, and my data seems to support it.

I’ll reply in full later, but for all readers’ benefit, here are the figures you posted to Imgur:

Unfortunately, WordPress does not allow commenters to upload images to their comments, and finding a trustworthy and effective plugin to get around that has eluded me. So sometimes I repost the imgur figures here for posterity and ease of following the back-and-forths in a comment thread.

I think the evidence supports the conclusion that your signal-generation code contains flaws. I don’t see any evidence, though, that your CSP estimation code has any problems.

These should not be present, for the reason I stated before involving the occupied bandwidth of any signal using square-root raised-cosine pulses. However, it does not appear that you are using square-root raised-cosine pulses for the SQPSK signal here, because sidelobes are clearly visible in the provided PSD plot, and true square-root raised-cosine pulse transforms do not possess sidelobes. The PSD for your square-root raised-cosine QPSK signal looks fine.

So that’s one signal-generation flaw for sure.

Turning back to the rectangular-pulse SQPSK signal, there is no mathematical justification for all the extra cycle frequencies in the provided plots (see The Literature [R1] and the post on PSK/QAM). These are highly likely due to incorrect implementation of the rectangular pulses in the inphase and quadrature components of the complex-valued signal, including their relative timing and the length of each individual pulse. A hint there is that you already mentioned that creating fractional-symbol-interval rectangular-pulse SQPSK was difficult.

Moreover, all measurements I’ve already published to the CSP Blog, as well as some below in this reply, are consistent with the fact that the non-conjugate cycle frequencies for rectangular-pulse SQPSK are equal to even multiples of the symbol rate and the conjugate cycle frequencies are equal to

and the conjugate cycle frequencies are equal to  . These features are a subset, exactly, of the features for rectangular-pulse BPSK (see the Gallery for pictures).

. These features are a subset, exactly, of the features for rectangular-pulse BPSK (see the Gallery for pictures).

I’ve estimated the cyclic-domain profiles for the three signals and plotted them in a style similar to yours. The SCFs are plotted directly, the coherences are plotted logarithmically. I did this for two versions of each of the three signals. The first has integer symbol interval . The second has fractional

. The second has fractional  (here the symbol rate is

(here the symbol rate is  ).

).

OK now we are getting somewhere! Your insight led you to the conclusion that the difference is in the signal generation method, and I agree. You were correct about my SRRC pulse shape having a bug. I was using the wrong pulse duration (by one-half) when I was doing SQPSK (I was using the offset time by mistake). This shorter pulse shape has a wider bandwidth, hence the sidelobes in the PSD outside what the occupied bandwidth should be. Great catch!

As to the discrepancy with the rectangular pulse shape, I believe the unexpected results are due to, of all things, a disagreement on what a rectangular pulse is!

Let me illustrate what I mean with a simple example, a BPSK signal sampled at 2.5 samples per symbol. As I stated previously, my signal generator uses a mathematical definition of the waveform, sampled at specified times. So BPSK is (pardon the sloppy notation) An*rect(t-nT) or An*(step(t-nT) – step(t-nT+T)) where An are the symbols {-1,1}. This waveform has instantaneous phase transition times, and so infinite bandwidth. The blue plot shows the result of sampling this waveform at a rate of 2.5/T, so the symbols alternate between 2 and 3 samples per symbol, with a value of either 1 or -1, (0 or 180 degrees).

The red plot shows the same waveform (with different AWGN) sampled at 5 samples/symbol, and then resampled by p/q = 1/2 with a 84-tap polyphase FIR filter, via the matlab function y = resample(x,1,2,21). This is obviously a band-limited waveform, and the sample values are interpolated between 1 and -1 by the filter.

The PSD of these two waveforms are obviously different, and this leads to different SCF. For the resampled waveform, the higher frequencies have been filtered away. However, for the directly sampled waveform, the higher frequencies remain, and in fact are aliased back in over the entire discrete bandwidth. I would venture to propose that this explains the extra peaks in the SCF that I am getting.

So the question becomes which waveform is a rectangular pulse waveform? To each his own, I suppose, but it depends what one is intending to model. I think this really highlights the point that one must be careful how one deals with signal data. Using an interpolation filter to resample data could lead to data that is more narrowly band-limited than the transmitter being modeled would likely generate. Conversely, assuming an ideal (a/k/a textbook) waveform with infinite bandwidth isn’t modeling a realistic transmitter.

Another interesting example of this issue crops up for OFDM signals. The textbook model of an OFDM waveform is simply modulating a set of critically-spaced subcarriers (tones) with a set of complex symbol values. An actual OFDM transmitter calculates the IFFT of the symbols and uses these values for the DAC followed by a reconstruction filter. These two models are equivalent only for an ideal reconstruction filter, which can’t actually be realized. So anyone that models OFDM as complex subcarrier tones (as most papers do) is technically wrong, but this does not necessarily invalidate their results.

So in conclusion, when I generate data at 10 samples per symbol, I get results that match your integer rate examples, and when I resample that data (e.g. y=resample(x,21,20)) I get results that match your fractional rate examples.

Thanks for taking the time to provide your feedback!

https://imgur.com/a/t8fmnvo

Glad we are making progress.

I think this is true of all signal simulators.

Well, you probably won’t be surprised to hear that I don’t believe that. We should strive for correctness and agreement about correctness. Rectangles aren’t up for debate as far as I can see.

What I am trying to model is the uniformly sampled (equal time spacing between samples) waveform corresponding to a rectangular-pulse BPSK, SQPSK, or QPSK signal. That is, the signal as embodied by an electromagnetic field impinging on an antenna or the resulting induced voltage in the front-end of the radio system is a rectangular-pulse signal regardless of our sampling of that field or voltage.

If we obey the sampling theorem, we can sample at any of an infinite number of sampling rates and be sure we have captured all the information contained in the signal. That is, with those samples, we can, in principle, recreate the original analog waveform exactly.

The cyclostationarity of the discrete-time signal is determined by that of the analog waveform unless the sampling of that waveform somehow distorts or imparts new periodic or cyclostationarity components. That is not the case in practice. So if there are extra cycle frequencies in the sampled data, then the signal is not correctly constructed in the sampled-data simulator (relative to the objective I describe above).

The new figures you placed on imgur show that you are not obeying the sampling theorem (even approximately) for the rectangular-pulse signal (the distortion in the main lobe of the signal is evident).

And also that your mathematically generated signal has extra cycle frequencies that are artifacts of your math:

If you don’t want to reconcile your “5 samp/sym resampled by 1/2” with your “2.5 samp/sym” cycle-domain profiles on imgur, then I’m not sure how to proceed. That is what I would focus on.

Here are the PSDs for the signals I used to create the cyclic-domain profiles above. Note that the rectangular-pulse signals need to be sampled at a higher rate relative to the symbol rate to ensure we meet (at least to a good approximation) the sampling theorem’s condition that the sampling rate be at least twice the highest significant frequency component of the data.

Thanks again for pointing out the error in my SRRC pulse shaping in my OQPSK signal. That bug has gone unnoticed for quite some time!

I think the discussion on the fractional sampling approach is interesting. Yes a rect is a rect in the analog domain, but there are different ways to sample it. You (and most people) want uniformly sampled signals. I want to be able to specify arbitrary non-uniform sampled signals. Again, this allows me to simulate the time-dilation effect of moving transmitters and receivers. For example, a moving radar target will impart effects on the signal due to its relative velocity and acceleration which are not realistically modeled by a simple Doppler shift in frequency (not to mention the Doppler-shift model only works for narrow-band signals). But if I calculate the path delay as a function of time, I can model the effect of relative motion via non-uniform sampling of a model of the transmitted waveform. This allows me to estimate the target velocity and acceleration or detect artifacts imparted by target rotation, etc. Using P/Q resampling can only impart a constant relative velocity on the signal data, which does not meet my needs. Note that the amount of time dilation is relatively small, so the signal is nearly uniformly sampled.

Contrast this with the use case of generating 2.5 samples per symbol, which would be extreme motion indeed! If the signal is infinite in bandwidth, then having alternating 2/3 samples per pulse is correct. And this does impart additional cycle frequencies in the sampled data. Using P/Q resampling only works because of the reconstruction filter. Note that your fractional sampled PSD does not have a sidelobe between 0.4 and 0.5 Fs due to this reconstruction filter. So the data does not have additional cyclic frequency artifacts due to fractional resampling, but any true cyclic frequency that was in that 0.4-0.5 range is also now gone, right? So what is better? Obviously if you are looking for true cyclic frequencies, introducing false ones into the data is a big problem, as you end up with non-sensical SCF plots like the ones I generated. I was sure I had a problem with my SCF code, but it was correct!

Going back to the sampling theorem, it is only valid for band-limited signals. The ideal rect pulse has infinite bandwidth. No signals in the real world that I’m aware of have infinite bandwidth. Where we have to be careful is when we violate the sampling theorem by under sampling the data. Clearly the case where I have sampled the rect pulse at 2.5 samples / symbol I have violated the sampling theorem. But bandlimiting the data to 0.8 Fs may not be the right thing to do either. Suppose you are transmitting a very narrow pulse, where you are depending on the excess bandwidth to achieve very sharp rising and falling edges. Careless resampling of this data would broaden the transition times. Fundamentally (as you point out), you need to be cognizant of the bandwidth of your data before you go transforming it.

You might think that oversampling the rect pulse data would eliminate the cyclic artifacts, but it doesn’t. For example, if I generate data at 10.5 samp/sym, there are artifacts. Data generated at 10 and then resampled at 21/20 has no artifacts. But data generated at 21 and then resampled at 1/2 has artifacts but only at |alpha| > 0.4. Which just goes to show that ideal rect pulses have significant energy at very wide bandwidths.

Of course you know all this, which is why you said “… the rectangular-pulse signals need to be sampled at a higher rate relative to the symbol rate to ensure we meet (at least to a good approximation) the sampling theorem’s condition that the sampling rate be at least twice the highest significant frequency component of the data.” But I think you would also agree that your bandlimited data is not actually generating rectangular pulses. That is what I meant by (a bit flippantly) saying that we don’t agree on what a rectangular pulse is. What I should have said is that a sampled pulse can never be truly rectangular, which I think we agree on, and we can disagree on what constitutes the significant frequency components.

Hope I explained myself adequately. Thanks again for your insights!

What was the relative speed between transmitter and receiver for the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal you use in your previous comment?

Radar targets can move quickly, 1000 m/s = 2237 mph. So the relative Doppler shift df = 2v/c fc or only 6.7e-6 of the carrier frequency for a narrowband waveform. Of course the Doppler shift is a function of frequency so this simple frequency shift model doesn’t work well for wideband signals, hence my preference for time dilation via non-uniform sampling (in addition to modeling non-uniform motion).

I’m not sure I was clear in my question.

For the data records that you created and processed to produce the BPSK cyclic-domain profiles in this comment, what was the Doppler effect that was applied? In that comment, concerning two different methods you used for creating rectangular-pulse BPSK signals, I see no discussion of applying any Doppler effect (simple shift or otherwise). You called it a “simple example” and used it to illustrate the fact that the two different methods produce different sets of cycle frequencies (the point in contention).

Therefore I expected the answer to my question to be “zero.”

You are correct, there was no Doppler added to the example signal. It was simply the result of sampling an infinite-bandwidth continuous-time BPSK signal at a sample rate equal to 2.5 times the symbol rate. My contention is that this process will lead to additional cyclic frequencies, which as you point out are due to the aliasing of the sampled signal not meeting the Nyquist criterion.

The whole Doppler discussion was just to point out why I use non-uniform sampling.

Another note on the CS of LTE. I did use the CS of captured LTE signals in my “tunneling” work (My Papers [43]). The cycle frequencies I used for the known-type tunneling algorithm for LTE were 2, 4, 6, and 8 kHz, which are related to the framing [I think] of the LTE signal (and so are associated with multiple-access features rather than directly a consequence of the OFDM waveform). That is, OFDMA can be different than the underlying OFDM signal.

I created a plot showing the exploitable CS for captured LTE for another commenter a while back. Here is the plot: