Let’s look into the statistical properties of a class of textbook signals that encompasses digital quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM), phase-shift keying (PSK), and pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM). I’ll call the class simply digital QAM (DQAM), and all of its members have an analytical-signal mathematical representation of the form

In this model, is the symbol index,

is the symbol rate,

is the carrier frequency (sometimes called the carrier frequency offset),

is the symbol-clock phase, and

is the carrier phase. The finite-energy function

is the pulse function (sometimes called the pulse-shaping function). Finally, the random variable

is called the symbol, and has a discrete distribution that is called the constellation.

Model (1) is a textbook signal when the sequence of symbols is independent and identically distributed (IID). This condition rules out real-world communication aids such as periodically transmitted bursts of known symbols, adaptive modulation (where the constellation may change in response to the vagaries of the propagation channel), some forms of coding, etc. Also, when the pulse function is a rectangle (with width

), the signal is even less realistic, and therefore more textbooky.

We will look at the moments and cumulants of this general model in this post. Although the model is textbook, we could use it as a building block to form more realistic, less textbooky, signal models. Then we could find the cyclostationarity of those models by applying signal-processing transformation rules that define how the cumulants of the output of a signal processor relate to those for the input.

The original RF signal is the real part of the analytical signal when the parameter is actually the RF carrier frequency. Let’s distinguish the carrier offset in (1) from the RF carrier frequency by calling the latter

. Then the RF signal is given by

When the RF signal is downconverted (shifted in frequency), perhaps in multiple stages involving several shifts that sum to near , and the signal is otherwise undisturbed, then the model (1) holds for the result, where

is the difference between the actual RF carrier

and the effective (total) frequency shift. So, if the reception of the signal, and its downconversion, is of high quality, then the carrier offset frequency

is small compared to the bandwidth of

: the signal is very nearly downconverted all the way to zero frequency. We still refer to it as a carrier frequency sometimes, even though it is really an offset frequency. Ideal or ‘perfect’ downconversion corresponds to

.

To recap, the complex signal representation (positive-frequency signal representation) for the RF signal and the complex signal representation for the baseband signal differ only by the value of the carrier phase and by the value of the carrier frequency. For the RF signal, the carrier frequency is , and it is very large with respect to the bandwidth of

, and for the baseband (complex envelope) signal, it is small compared to the bandwidth of

, and is ideally zero.

So this means we can analyze the complex-envelope representation, and the results will easily translate to the analytic-signal representation, which is essentially the RF signal.

Cyclic Cumulants of DQAM

Let’s first assume perfect downconversion, that is, let’s set ,

, and

to obtain the complex-envelope (baseband) model given by

It can be shown that the th-order cyclic temporal cumulant function (cyclic cumulant) for the DQAM model (3) with IID symbols is given by (My Papers [6,13])

In (4), the key parameter is the cumulant for the symbol variable, which we call . This is the cumulant for

of order

using

conjugations. Such a cumulant can be computed by hand, or numerically, provided that the probability mass function for the discrete random variable

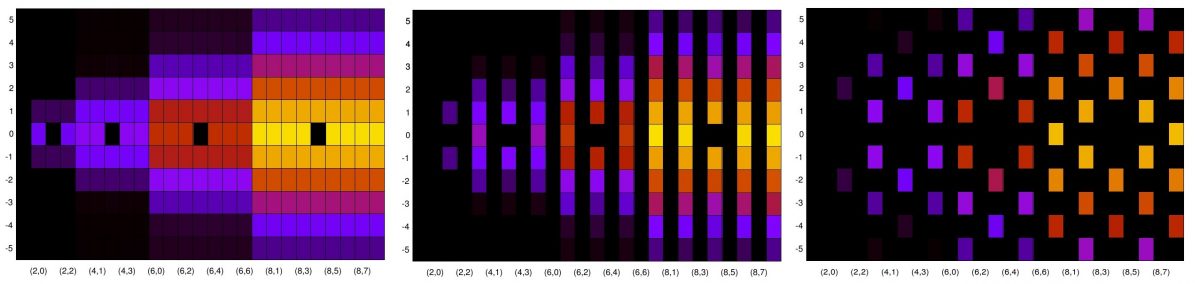

is known. But that probability mass function is just the constellation with equal probability given to each constellation point. So, we can compute those values. Let’s first look at some constellations:

For plotting purposes, the shown constellations are normalized so that the maximum of the real and imaginary parts are equal to . For the desired computations of moments and cumulants, discussed below, the constellations are normalized so that their variance is

.

By applying the usual cumulant machinery, involving lower-order moments and the partitions of the set , we can compute the exact values of the cumulants

. And of course we can compute the moments too. Here are the cumulants and moments for the real-valued constellations above (BPSK, 4ASK (4-level PAM), and 8ASK),

and the cumulants for some of the complex-valued constellations are shown in the following table:

All of the complex-valued constellations considered in Table 2 give rise to signals that exhibit no cyclostationarity for order with

or

. Moreover, the signals possess only three second-order cycle frequencies for

, which are

, if we assume a typical bandwidth-efficient pulse like square-root raised-cosine. That is, if I had bothered to create columns for

, the entries for

would be zeros, and the entries for

would be

.

The reduced-dimension cyclic temporal cumulant function is obtained from the cyclic cumulant by setting one of the lag values to zero, say . For clarity, this reduced-dimension function for digital QAM/PSK is given by

for cycle frequencies .

Cyclic Polyspectra of DQAM

The cyclic polyspectrum is the dimensional Fourier transform of the reduced-dimension cyclic cumulant function (5). The cyclic polyspectrum for DQAM/PSK is given by

for cycle frequencies .

To obtain the exact expressions for the cyclic cumulant and polyspectrum for the more general complex representation (1) that includes imperfect downconversion and unknown delay (that is, ,

, and

can all be different from zero), we can apply input-output relationships for basic signal processing operations. The residual carrier offset is just the multiplication of the baseband signal by a complex sine wave, and the delay

is just a, well, delay, which is easily represented by a simple linear time-invariant system. This exercise leads to the following conclusions regarding the general form for the cycle frequencies for DQAM:

If we let range over all the integers, we obtain the largest possible set of cycle frequencies for DQAM. This set is actually achieved by the textbook rectangular-pulse BPSK signal, which has infinite bandwidth, and so has an infinite number of cycle frequencies for each

combination, provided

is even.

In practice, the constellation for and the pulse function

limit the number of cycle frequencies and determine which ones are actually exhibited by a signal. For example, the odd-order moments and cumulants of the symmetric constellations above are zero, so the cyclic cumulants for DQAM are zero for all odd orders

. Real-world signals typically use a bandlimited pulse function

, such as the square-root raised-cosine pulse, and this severely limits the range of

. For

, we have

for such pulses.

Specialization to Second Order ( )

)

For , the

reduced-dimension cyclic temporal cumulant function reduces to a lag-shifted version of the usual non-conjugate cyclic autocorrelation function,

and the cyclic polyspectrum is a frequency-shifted version of the non-conjugate spectral correlation function,

Let and rewrite (9),

which is the formula one can find in various references (The Literature [R1, R47]). Similarly, for we have the cyclic polyspectrum (conjugate spectral correlation in this case) of

Making the same substitution as before, , we obtain

which is also consistent with a frequency-shifted version of the conjugate spectral correlation function for DQAM.

These cyclic polyspectrum formulas provide insight into the maximum cycle frequencies that can exist for DQAM. The cyclic polyspectrum is seen to be the product of shifted pulse-function transforms. When the transform is bandlimited (zero outside of some finite frequency interval), as it is for square-root raised-cosine pulses, then there is a largest

that can result in overlap between the factors in the transform-product.

For example, when considering the square-root raised-cosine pulse type, we know that it has maximum width of for roll-off factor of

, and minimum width of

for roll-off factor of

. The cycle frequencies are

. For roll-off of

, then, only

can produce overlap between the two shifted pulse transforms in the cyclic polyspectrum (spectral correlation) formula. That is, DQAM with roll-off of

has no non-trivial non-conjugate cycle frequencies. On the other hand, for roll-off of

,

will result in overlap. Similar remarks can be made about the conjugate spectral correlation function (cyclic polyspectrum for

above).

Estimates

Here let’s show some estimated cyclic cumulants and cyclic polyspectra for various orders and numbers of conjugated factors

for the DQAM/PSK constellations that we graphed above.

We start with the basics–the power spectra. The FSM is used to estimate the power spectra for simulated versions of the DQAM/PSK signals. All signals employ symbols that are independent and identically distributed (IID), and the pulse functions are square-root raised-cosine with roll-off of (excess bandwidth of

%), carrier-frequency offset of

, and

samples. The PSD estimates are shown below:

The thing to notice is that when all the signals have the same average power, the same pulse function, and IID symbols, their power spectra are identical. From the point of view of, say, modulation recognition, this is not a good outcome. The signals cannot be distinguished from each other.

Here are plots of the estimated non-conjugate spectral correlation function for the symbol-rate cycle frequency:

As expected, these spectral correlation functions are identical. Now consider the conjugate spectral correlation for :

Here we see that the three real-valued constellations, BPSK, 4ASK, and 8ASK, have non-zero spectral correlation, while all the complex-valued constellations do not. Finally, then, there is some basis for distinguishing some of the signals from others based only on second-order statistics. Yet distinguishing between BPSK, 4ASK, and 8ASK remains impossible at second order.

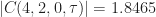

Enter the cumulants. From the table above, we know that starting with order , the cyclic cumulants begin to take on different values for different constellations. Here are the

cyclic cumulant magnitudes for

:

Not all the modulations have distinct cyclic cumulants here. In particular, QPSK, 8PSK, and 16PSK all have identical cumulants (see the table above). But many do have distinguishable cumulant values.

Here are the estimated cyclic cumulants for and

:

Finally, just for fun, here are several sets of estimated sixth-order cyclic cumulants:

The jpeg and MATLAB .fig files are posted in the Downloads page.

Discussion

What’s important about the cyclic cumulants for DQAM/PSK is that there is always some order for which they differ for any two distinct constellations. This idea has its roots in the fact that the sets of

th-order probability density functions for the two signals must differ for some

, else the two signals are actually the same random process.

Now, an individual selection of may yield identical cyclic cumulants for multiple

even for distinct signal constellations. However, when we look at the sets of cyclic cumulants over a number of

,

, and

, we can still obtain distinguishing features. For example, for QPSK and 8PSK, the

cyclic cumulants are identical. As are the

cyclic cumulants. But the

cyclic cumulants are not identical, and QPSK can be distinguished from 8PSK by the presence or absence of the

cyclic cumulant for

.

Now there are two (at least) pieces of bad news. The first is that distinguishability for a pair of constellations may require a very large value of indeed. Estimating moments and cumulants for large

is a computationally challenging task. The second is that the differences between the cumulants may not be all that large when they do occur for a relatively small value of

, meaning distinguishability will be difficult except for in very high SNR situations.

In My Papers [25,26,28] I lay out one approach to exploiting the fact that sets of cyclic cumulants differ to create interference-tolerant and quite general modulation recognition algorithms. When combined with blind processing that is based on the strip spectral correlation analyzer, we’re on our way toward true RF scene analysis.

Application to More Realistic Signal Models

This post has considered textbook signals of the DQAM and PSK type. Are there really any out there? (I asked here if you want to add your opinion or experience.) There are some real-world effects that plague DQAM signals that could be addressed using the basic constellation-based formalism described here. Any transmitter imperfection that results in a constant distortion of the constellation simply results in a new constellation, and that new constellation has its own values. For example, a power imbalance in the inphase and quadrature channels of the transmitter will stretch or compress the constellation points along either the

or

dimension in the constellation plots at the top of this post.

Some realistic signal models may combine textbook DQAM with slotting or framing or departures from IID symbols, and these signals may be mathematically representable in terms of signal processing operations involving the DQAM textbook signal and one or more other signals. The post on signal processing operations might then be helpful.

So for equation 5, you can calculate the cumulant for the modulation constellation directly and then with knowledge of the pulse shape, you can determine what the cumulant will be for a given rolloff factor? For modulation recognition, how would you use this equation?

I assume that blind recognition, you would perform a cyclic cumulant using the moment to cumulant formula, and look for a peak? Could you then compare the peaks somehow to the value given from equation 5? Would the value of the peaks at the k/T_o symbol rate harmonics correspond somehow as well?

Also for equation 5, if p(t) is the pulse shape, and the raised cosine pulse shape is band limited to 1/(2*T_o), wouldn’t evaluating it at k/T_o essentially be zero or very close to zero, regardless of the rolloff factor, even at 100% excess bandwidth? When I try to calculate these values, I am getting values that are essentially 0.

Also I calculated most of the cumulants using the moment to cumulant formula, and I get most of the values you show, though for QPSK C(4,0) I get -1, not 1 as your table shows. Perhaps I am not calculating it correctly, but it looks like all the other values appear right.

For example this matlab code:

>> bits = randi([0,1],2^16, 1);

>> h = comm.QPSKModulator(‘BitInput’, true);

>> mod=step(h,bits);

>> mean(mod.^4) – 3*(mean(mod.^2)).^2

ans =

-1.0000 + 0.0000i

Thanks for your posts, I have enjoyed working through them!

I appreciate the kind words, aapocketz. You asked a lot of questions in that comment!

I’m not going to answer them all in one reply to the comment, though, because I would get too tired.

So let’s take that last one first. You calculated a symbol-variable cumulant for QPSK that differs from the one I posted in the table. However, the cumulants I posted in the table under the name “QPSK” correspond to the plot labeled “QPSK” in the constellation picture toward the top of the post. That constellation has points at (1, 0), (0, i), (-1, 0), (0, -i). I believe the values in the table are correct for that “QPSK”. So the question is whether “comm.QPSKModulator” uses the same constellation. I bet it doesn’t. I bet it uses what I call “4QAM”, which is a square constellation version of my QPSK constellation. You can see in my table that the (n,m) = (4,0) symbol-variable cumulant for THAT constellation matches yours, -1. Can you reply with the constellation points implied by your MATLAB code snippet? Thanks!

Thanks I didn’t notice that difference, yes matlab assumes pi/4 phase offset, using 0 phase offset I get the value you have referenced.

Yes, exactly. The plots I provided later in the post are estimates, though, not evaluations of (5).

See My Papers [25], [26], and [28] for ideas. The key idea is “cyclic cumulant matching”, where measured cyclic cumulants are correlated with stored ideal ones (from (5)). Each distinct modulation type would have its own stored cyclic cumulant functions. That approach is optimal, in a sense ([26]), but computationally demanding. To make things more computable, one might severely restrict the range of the delay vector (tau) in the cumulant matching operation.

I’m not sure I understand the question here. I think you’re wondering how to do a comparison between measured and ideal cyclic cumulants if you don’t know the signal’s cycle frequencies in the first place. You could use second-order processing (SSCA for example) to find the symbol rate, and look for the quadrupled carrier in the fourth-order lag product. That would give you enough to proceed.

Well, the roll-off factor of zero results in a pulse transform P(f) that is bandlimited to [-0.5/T_0 +0.5/T_0], with total width of 1/T_0. However, (5) deals with p(t), not P(f). You can see from the discussion just above the heading “Estimates” that when the roll-off is zero, there is no symbol-rate cycle frequency. So, yes, when you use the roll-off of zero to create a SRRC p(t), and evaluate (5) for alpha = 1/T_0, you should get zero. But when you have roll-off of 1, you should get a strong cyclic cumulant for both alpha = 0 and alpha = 1/T_0.

When you use your roll-off of 1 (100% EBW) to create p(t), then use that p(t) to create a textbook QAM signal, do you see a non-zero cyclic autocorrelation estimate for alpha = 1/T_0? If not, I think maybe something is wrong with your p(t).

Hope this helps! Thanks again for the great questions. I’m sure our dialog will help others too.

I am still confused about the nature of equation 5, after reading your papers and a couple by Dobre.

1. what is p(t)? I was assuming this was the pulse shaping function, essentially the impulse response of the raised cosine filter.

2. What is the point of conjugated p(t) since the RRC impulse response is real valued?

3. It appears in your plots that the maximum occurs for all modulation types at tau1,tau2,..tauN = 0, so for n=2 doesn’t that mean just squaring the pulse shape?

For example, this matlab code generates small values and for higher values of n it approaches zero.

>> samples_per_sym = 10;

rolloff = 1;

p_of_t = rcosdesign (rolloff, 30, samples_per_sym);

cyclic = exp(-1j*2*pi*(1/samples_per_sym).*(1:length(p_of_t)));

sum(p_of_t.^2.*cyclic)

sum(p_of_t.^4.*cyclic)

ans =

0.2575 – 0.1871i

ans =

0.0518 – 0.0376i

4. If the above is true, how does any of this apply to modulation recognition? You would need apriori knowledge of the transmitted symbol rate and the pulse shape (at least the rolloff factor) to calculate any of this. You could possibly recover the symbol rate, but not sure about the rolloff.

5. The way to calculate the cumulants for a sampled signal is to use the moment to cumulant formula, and for cyclic cumulants, the cyclic moment to cumulant formula or CTCF (from this post https://cyclostationary.wordpress.com/2016/02/14/cyclic-temporal-cumulants/). If you are comparing a sampled data set to some known theoretical signal, why wouldn’t you use the moment-cumulant formula on a simulated theoretical signal to use to compare to the sample data?

Good questions! And I’m glad you’re looking so deeply into the topic.

Some answers:

Yes, it is the pulse-shaping function. The nature of p(t) depends on the propagation channel between the transmitter and the receiver. If that channel is an impulse, then the received signal will be modeled as a DQAM signal with the same p(t) that the transmitted signal uses (no distortion of the signal is imparted by the channel). Otherwise, the received-signal p(t) may differ from that used by the transmitter.

Yes, the conjugations applied to p(t) are superfluous if p(t) is real. For generality, I keep the conjugations around. A propagation channel with a frequency-selective nature can have a transfer function that is not symmetric about the RF carrier, resulting in a received signal with a new pulse q(t) that could be complex-valued. (Agree?)

Right, but you haven’t actually computed the cyclic cumulant yet, you’ve just computed the integral (sum) involving the product of pulse-shaping functions. You still need the factor in front, C_a(n,m)/T_0. Once you choose p(t), T_0, and C_a(n,m), you’ve effectively specified the average power of the signal, and you can compute the cumulant and say ‘this is the cyclic cumulant value for a DQAM signal with such-and-such constellation, pulse p(t), and average power P_s.’ All my plots in the post are for DQAM/PSK signals with average power of 1. This means that the signal is scaled if need be to achieve that power level. The scaling can be associated with a scaling of the constellation or a scaling of the pulse-shaping function. In the end, I claim the combination of the pulse-factor you are computing and the symbol-variable cumulant causes the cyclic cumulant magnitudes for DQAM to increase with order n provided the power level is 1.

I hope you had a chance to look at My Papers [25], [26], [28]. Well, one form of the problem would involve having prior information about the rate and the carrier frequency, yes. Another would be to blindly estimate the rate using exhaustive CSP (SSCA for example), and the fourth-order (4, 0) moment function, which has an additive sine wave with frequency 4f_c for most of the DQAM signals. To handle the excess bandwidth, you might have theoretical-signal catalog entries that correspond to a set of roll-offs of interest.

If everything I’ve been saying is correct, the DQAM cyclic cumulant formula should be consistent with the moment-to-cumulant approach. If you are very careful, you should get good agreement between the theoretical formula and a high-quality high-SNR estimate formed from the correct combination of lower-order cyclic moments (each of which will have some estimation error attached to it). So, I agree with you—one could do that. In fact, you might have to resort to it for signal types for which we don’t have a good theoretical formula.

Thanks this have been very helpful. I found that if I set the gain of the raised cosine filter to sqrt(samples_per_sym) I get the unit power signal, and I don’t have the vanishing cumulant issue. Other things you said make sense too, it helped to clarify things. I tend to get stuck in details, and it helped me work through it. Thanks for the help!

I really enjoy reading your blog, always clear and informative ! ) as an example. If the roll off is 0.5, then we have only three cyclic frequencies for

) as an example. If the roll off is 0.5, then we have only three cyclic frequencies for  , which are

, which are  , where

, where  refers to the symbol rate. Am I right?

refers to the symbol rate. Am I right?

Following from aapocketz discussion, now we have computed the theoretical cyclic temporal cumulants (CTC) using equation (5). Now we have to estimate the CTC from the received data using the cyclic version of moments to cumulants conversion. Let’s take the SRRC BPSK (without frequency offset

So, to compute the CTC for , we have to estimate the cyclic moments (R) of order 2 for

, we have to estimate the cyclic moments (R) of order 2 for  which sum to

which sum to  , and substract their procducts from the 4th order cyclic moment, such that:

, and substract their procducts from the 4th order cyclic moment, such that:

where![\tau=[0\ \tau_1\ \tau_2\ \tau_3], \tau^\prime=[0\ \tau_1], \tau^{\prime\prime}=[\tau_2\ \tau_3]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ctau%3D%5B0%5C+%5Ctau_1%5C+%5Ctau_2%5C+%5Ctau_3%5D%2C+%5Ctau%5E%5Cprime%3D%5B0%5C+%5Ctau_1%5D%2C+%5Ctau%5E%7B%5Cprime%5Cprime%7D%3D%5B%5Ctau_2%5C+%5Ctau_3%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=1a1a1a&s=0&c=20201002) . Am I right ?

. Am I right ?

Last question, is it possible to comment using Latex syntax for equations ? I think it would be better than the notation I used above.

Before I attempt to answer your technical question, let me answer your WordPress.com question. You should be able to use latex in your comments. When you want to typeset some math, use the following coding: $ followed by the word “latex” (no quotes) followed by your latex code, followed by $.

To get that integral above, place a dollar sign at the beginning and end of this

fragment:

latex \int_{-\infty}^\infty} f(x) dx

Or inline, like this by adding leading and trailing dollar signs to latex T_0. I edited your comment and replaced your $f_0$ with

by adding leading and trailing dollar signs to latex T_0. I edited your comment and replaced your $f_0$ with  and it appears to work.

and it appears to work.

However, once you submit a comment, you cannot edit it. This is a WordPress.com limitation; I can’t turn it on and off.

If you agree, I can go in an change the rest of the math without changing any of your content. What do you think?

Yes.

Not quite right. You must consider the set of second-order cycle frequencies that you identified earlier, which is , not

, not  . Then your formula

. Then your formula

is too simple. You need to consider each partition of and find the associated lower-order cyclic moments for the delays

and find the associated lower-order cyclic moments for the delays  implied by the partition. For each set of those lower-order cyclic moments for which the cycle frequencies add to your target fourth-order cycle frequency of zero, multiply them together and weight them according to the moment-to-cumulant formula. That means there could be more than one product of lower-order cyclic moments for a given partition.

implied by the partition. For each set of those lower-order cyclic moments for which the cycle frequencies add to your target fourth-order cycle frequency of zero, multiply them together and weight them according to the moment-to-cumulant formula. That means there could be more than one product of lower-order cyclic moments for a given partition. cyclic cumulant.

cyclic cumulant.

Note that you must also take into account the conjugations, which will depend on the partition as well. So even conjugate cycle frequencies can figure into the

I suggest reviewing the post on cyclic cumulants. You might benefit from reviewing the cyclic polyspectrum post too.

Sure, you can change the notation of my comment. Thank you.

Thank you for the clarifications, I see that I made some mistakes there.

1/ Considering the set {1,2,3,4} the possible second order partitions are {1,2}{3,4}, {1,3}{2,4} and {1,4}{2,3} . While in my comment I considered only {1,2}{3,4}.

2/ for the set of second order cyclic frequencies { }, for each partition, the cyclic frequencies which sum to

}, for each partition, the cyclic frequencies which sum to  (my target cyclic frequeny) are: {

(my target cyclic frequeny) are: { } and {$0, 0$}.

} and {$0, 0$}.

Now, setting the number of symbols to 4000 and $T=10$, I can get using the cyclic moments to cumulants conversion where

using the cyclic moments to cumulants conversion where ![\tau=[0 0 0 0]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Ctau%3D%5B0+0+0+0%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=1a1a1a&s=0&c=20201002) . Using equation (5) for the same configuration (n=4,m=2,

. Using equation (5) for the same configuration (n=4,m=2, and

and  ), and scaling the pulse shape function to get an average power of 1 (as explained in the comments above), the theoretical magnitude is 1.8498. The theoretical results match the estimated ones for other congigurations as well, (for now using the SRRC BPSK signal).

), and scaling the pulse shape function to get an average power of 1 (as explained in the comments above), the theoretical magnitude is 1.8498. The theoretical results match the estimated ones for other congigurations as well, (for now using the SRRC BPSK signal).

Great blog !

Dear Colleagues,

I need your help and I hope someone could tell me how to solve it.

First of all, I’m working with software defined radio NI USRP-2922 and thank’s to Modulation Toolkit i can work with digital modulated signal with given symbol rate, samples per symbol, constellation etc. Received, complex signal in baseband is given to function calculating statistical moments as in attachment M_pq=E(y^p (y^*)^(p-q)). Y is complex signal as I mentioned above. In literature there are well described expresions calculating higher order cumulants based on previously described moments. I expected that achieved values would be similar as in this article. Unfortunately my results were different. First thing is that my cumulants are complex (apart C21 what is obvious), and in all publications there are only real values. I’ve tried to calc. module, or only real part of signal. Currently I have no idea how to solve this problem. Probably mistake is in my code (I also tested it in ideal data – results were the same).. For me is hard to understand that our reasults are only real, when complex value to the power of 2 is: (a+jb)^2 = a^2 + j2ab – b^2, so it’s still complex. I hope that you would have few minutes to explain me this phenomena, I would be very grateful.

Thanks for the comment, Karol.

We have to distinguish between the cumulants for the complex-valued constellation random variable and the cumulants (and cyclic cumulants) for a complex-valued sampled signal. Mostly what you see published are the cumulants and moments for the constellation random variable, and these are typically real-valued due to the symmetric nature of the constellations. On the other hand, when you capture complex-valued data from your USRP, any moments and cumulants you estimate will be subject to carrier-frequency offset (the signal might not be *exactly* at zero frequency), other impairments such as inphase-quadrature crosstalk, and of course complex-valued noise. Moreover, there is an effective pulse-shaping function, which itself may be complex. Finally, there is the matter of delay. Even if the formula for the cyclic cumulant for your QAM/PSK signal is real valued, if the signal model from which it derives has a delay with respect to the captured signal, you can have a complex cyclic-cumulant result.

So, there are a lot of reasons why your cumulant can be complex-valued when you might have expected it to be real-valued.

I recommend trying to compute a cyclic cumulant for the cycle frequency of the symbol rate (say, order 4) and compare the magnitude and phase of that cyclic cumulant to the formula in the post (equations (4) or (5)). It will be important to use the same pulse-shaping function in the USRP signal and in the formula. Typically we use square-root raised-cosine pulse shaping.

Dear Chad,

I’m trying to follow the cyclostationarity-based AMC. I was wondering if all the modulations listed in Table 1 and 2 are scaled with unity average power so the cumulant order of 2 is 1.

For example, the constellation for 4-ask is {0,2/sqrt(5),4/sqrt(5),6/sqrt(5)}

Yes.

Please note the paragraph in the post just below Figure 1. The scaling of the constellation points for the plots is different than that for the computation of the moments and cumulants. The variance of the constellation random variable is equal to the (2,1) cumulant of the constellation random variable except in the case where the mean of the constellation random variable is not zero (such as OOK).