To test the correctness of various CSP estimators, we need a sampled signal with known cyclostationary parameters. Additionally, the signal should be easy to create and understand. A good candidate for this kind of signal is the binary phase-shift keyed (BPSK) signal with rectangular pulse function.

PSK signals with rectangular pulse functions have infinite bandwidth because the signal bandwidth is determined by the Fourier transform of the pulse, which is a sinc() function for the rectangular pulse. So the rectangular pulse is not terribly practical–infinite bandwidth is bad for other users of the spectrum. However, it is easy to generate, and its statistical properties are known.

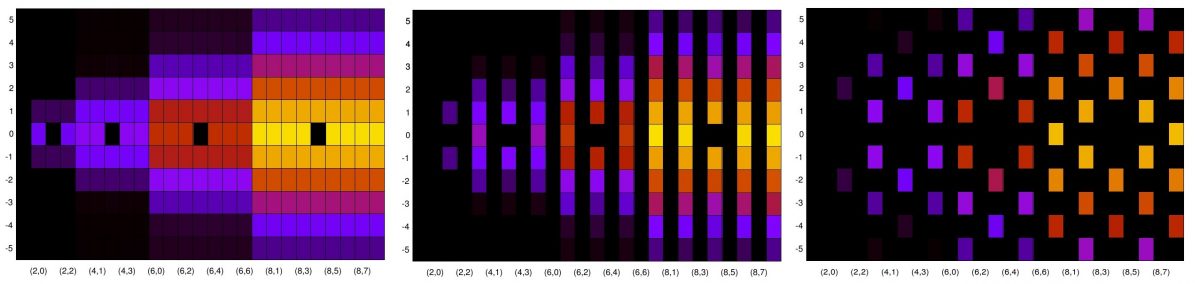

So let’s jump in. The baseband BPSK signal is simply a sequence of binary ( 1) symbols convolved with the rectangular pulse. The MATLAB script make_rect_bpsk.m does this and produces the following plot:

The signal alternates between amplitudes of +1 and -1 randomly. After frequency shifting and adding white Gaussian noise, we obtain the power spectrum estimate:

The power spectrum plot shows why the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal is not popular in practice. The range of frequencies for which the signal possesses non-zero average power is infinite, so it will interfere with signals “nearby” in frequency. However, it is a good signal for us to use as a test input in all of our CSP algorithms and estimators.

The MATLAB script that creates the BPSK signal and the plots above is here. It is an m-file but I’ve stored it in a .doc file due to WordPress limitations I can’t yet get around.

Hello,

Thanks for creating this blog.

I am supposed to work on applying deep learning methods for denoising or separating cyclostationary signals. My background is mainly in machine learning, image processing and computer vision. Since I am not from Digital Signal Processing or Digital Communication background, It would be great if you can recommend a or few resources to grasp the basics of these first.

Thank you for your interest in the CSP Blog!

I suppose since your background contains image processing, you do actually have a lot of the basics of DSP for communication-signal processing, such as transform theory, filtering/convolution, and perhaps even spectrum estimation. So I’m thinking what you are currently lacking is more in the areas of mathematical modeling of communication signals and the theory and practice of cyclostationary signal processing.

On CSP, check out my papers in My Papers and, perhaps more importantly, the papers on CSP in The Literature. You might also read/skim all the posts here at the CSP Blog, in their order of appearance (because I start out slowly and build up to more advanced topics).

For communication-signal modeling, a good textbook is Proakis (The Literature [R44]). I’m sure there are online things too. Perhaps Khan Academy?

Finally, for full disclosure, see evidence of my current attitude toward the Machine Learners and their foray into CSP:

Machine Learning for Modulation Recognition 1

Machine Learning for Modulation Recognition 2

Can a Machine Learn the Fourier Transform 1 and 2

Modulation Recognition Challenge to the Machine Learners

Hello Dr. Spooner,

I come from a data science background and have been trying to learn DSP / CSP with a focus on performing blind RF spectrum detection. I have successfully recreated the bpsk signal using rectangular pulse shaping.

However, I still can’t figure out the reason you zero pad your bit sequence to increase the length?

The length of the bit_sq = 4,000 whereas the length of the sym_seq = 40,000

When I use sym_seq = 40,000 I am able to recreate the PSD above with signal peak power of about 10 dB

When I do no zero pad the sym_seq and keep the length at 4,000, the shape of the PSD is similar but the peak power is higher at about 20 dB.

% Create symbol sequence from bit sequence.

sym_seq = 2*bit_seq – 1;

zero_mat = zeros((T_bit – 1), num_bits);

sym_seq = [sym_seq ; zero_mat];

sym_seq = reshape(sym_seq, 1, T_bit*num_bits);

Also, when you add noise to your signal: n_of_t = randn(size(x_of_t)) + sqrt(-1)*randn(size(x_of_t));

I assume you are trying to create complex noise of unit power. In this case, don’t we need to add a division by square root of 2 ?

Ref:https://pysdr.org/content/noise.html

Hey Cal! Welcome to the CSP Blog.

Well, I’m not really “zero-padding” the sequence, I’m simply converting the {0, 1} bits to {-1, +1} symbols and then effectively convolving those symbols with a rectangle with width 10. So the outcome of that little block of code is the pulse-modulated symbol sequence. I think I put a similar script on Downloads or the SQRC PSK/QAM post for generating a SQRC BPSK signal–comparison with that might help clear things up for you.

The full code snippet for the noise is:

n_of_t = randn(size(x_of_t)) + sqrt(-1)*randn(size(x_of_t));

noise_power = var(n_of_t);

N0_linear = 10^(N0_dB/10);

pow_factor = sqrt(N0_linear / noise_power);

n_of_t = n_of_t * pow_factor;

y_of_t = x_of_t + n_of_t;

where N0_dB is specified as -10 at the beginning of the script. So, no, not trying to make unit-noise power. You might want to look at the final cell of the file:

%% Check power of PSD against known sum of noise and signal powers.

meas_pow = sum(I) *(1.0/N_psd);

Power_linear = 10^(Power_dB/10.0);

fprintf('PSD-measured power is %.5e, known total power is %.5e\n', ...

meas_pow, N0_linear + Power_linear);

The total power of the generated sequence should be 1.1 = 1 + 0.1, since the unit-power signal has power 0 dB and the noise power should be 0.1 since we specified it as -10 dB. Is that what the script gives you on your end?

Thanks for the response.

Regarding the noise calculation, I think it makes sense to me now. It really does not matter if the noise is unity power or some other value.

After generating the noise vector, I am recomputing the noise power, finding the power factor and finally scaling the noise vector by the power factor.

noise = (np.random.randn(len(freq_shifted_data)) + 1j * np.random.randn(len(freq_shifted_data))) / np.sqrt(2)

noise_power = np.var(noise)

no_linear = 10 ** (no_dB / 10)

power_factor = np.sqrt(no_linear / noise_power)

noise = noise * power_factor

I estimated the PSD using the scipy welch function and the Total Power is same:

Expected Power: 1.1

Mesured Power with unit noise: 1.1095405808531402

Measured Power without unit noise: 1.1095405808531402

Yes! It does not matter what the initial power is for the complex noise. We’re normalizing it anyway (denominator of no_linear/noise_power) and then scaling it (numerator of no_linear/noise_power).

Regarding the companion script for making a square-root raised-cosine BPSK signal, see “6” on the Downloads page, which should be at this link. The extension is “.doc” but it is a MATLAB file (WordPress restriction work-around).

Ah, yes. It definitely did. The lines of code in my first comment are basically up-sampling the symbol sequence to obtain the required samples per symbol.

If I set num of symbols to 4 and samples per symbol to 3, my output is as follows:

Bit Seq [1 0 1 0]

Sym Seq: [ 1 -1 1 -1]

Sym Seq of Zeros: [0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

Sym Seq Up-sampled: [ 1. 0. 0. -1. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. -1. 0. 0.]

Hi Dr. Spooner.

This might be a really rookie question on dsp but your bpsk code mentions the power of the signal is 0 dB but you don’t use the power term anywhere in the code for generating the signal.

When we calculate total power of the signal plus noise you get the right answer with is 1 for signal and 0.1 for noise in linear scale.

What am I missing in understand the concept?

Not a rookie question, and I don’t think you are missing anything!

This is poor coding on my part. I knew the power was one, because I created the signal with rectangular pulses with unity heights and the symbols modulating those pulses were . So the squared magnitude of that signal (with or without the complex-exponential frequency-shifting factor that applies the carrier) is one. Therefore the energy over any period with length

. So the squared magnitude of that signal (with or without the complex-exponential frequency-shifting factor that applies the carrier) is one. Therefore the energy over any period with length  is

is  , and therefore the power is unity.

, and therefore the power is unity.

But I should have made all that explicit either in the code or in the comments.