Previous SPTK Post: The Characteristic Function Next SPTK Post: Wavelets

In this post, we take a look at a special linear time-invariant system called the matched filter. It is used to detect the presence of a known signal. In practice, it is often applied to the detection of a periodically repeated known portion of a communication signal, such as a channel-estimation frame or frequency-correction burst. It is also widely used in the detection of radar pulses, where the matched-filtering operation is renamed to pulse compression. Filtering, which implies a convolution operation, and correlation are nearly the same thing. Therefore applying a matched filter is sometimes referred to as applying a correlator.

Jump straight to the Significance of the Matched Filter in CSP.

Introduction

In many signal-processing situations it is desired to detect the presence of a known signal in noise–is the signal there or not? The crucial word in that last sentence is known. When we say known, we mean that we can write down the exact signal over some interval of length . If the data that we process does not contain, over some interval of length

, our signal, then the signal is not actually known. This can happen if the transmitted communication or radar signal does indeed contain the known signal, but somewhere between the transmitter and the receiver the signal becomes corrupted by linear or nonlinear effects such as multipath distortion, frequency shifting, the general Doppler effect, receiver impairments, sampling-rate error, etc.

We admit that we don’t know the starting point of the known signal-to-be-detected, and we can accept that it is subject to additive stationary noise. Moreover, we can accept an unknown complex scale factor to account for unknown signal power and unknown carrier phase.

Let denote the perfectly known signal of interest, and let

denote the data to be processed by our detector. The length of

is

and the length of

is

. We can represent our data by

where is the unit-height and unit-width rectangle function centered at

. I’m writing it this way, which I’ll simplify later, to emphasize the point that the matched filter will not only be a good detector of

, but it will also serve to estimate

, thereby localizing the occurrence of our known signal in time.

All filters are completely characterized by their impulse-response function, which is the output of the filter for an impulse input applied at time . All other possible outputs–no matter the input–can be calculated based on the input and the impulse-response function.

Denoting a generic impulse-response function with the usual symbol of and the filter input by

, the filter output is given by the convolution of the impulse response with the input,

Also recall that the frequency response of a linear time-invariant system is the Fourier transform of the impulse response, and characterizes the ability of the filter to modify (pass undisturbed, attenuate, amplify, phase-shift) individual frequency components of the input signal. The frequency response is often called the transfer function,

Derivation of the Matched Filter

Let’s consider the simplified continuous-time data model of

The known signal is and the noise-plus-interference is

. The Fourier transform of the signal is

and the power spectrum of the random noise/interference is

, which is assumed to never be zero within the support of

. This last assumption will certainly hold if there is a component to

that is white noise, and we will specialize our final result to the case where

is indeed nothing but white Gaussian noise.

Our question is this: What linear time-invariant system (filter) is optimal for presence detection of ? We seek the impulse-response function of a filter such that when the filter output exceeds some threshold, we declare the presence of the signal in some “best” way. As with most optimality-based signal-processing approaches, there are different options for defining “optimal.” What sense of optimality will we use here?

The output of our filter is denoted by ,

Let’s consider the output at time ,

. We want this number to have a large magnitude on hypothesis

and a small one on

. And we want that to be true on the average. Thinking of the tractability of optimization problems that involve quadratic functions of data, we can consider forming an SNR of sorts. The mean-square value of

(remember

is non-random, but

is a random process here, so that

is random),

We can define the SNR by the ratio of the mean-square values of

on the two hypotheses,

If the signal is absent (), then the denominator of

favors making

small. If the signal is present (

), the numerator favors making

large. So maximizing the SNR measure

is a way to find the “best” filter for detecting the presence of

. Let’s start with the denominator of

.

SNR Denominator

Let’s attempt to straightforwardly evaluate the expectation. Unless otherwise specified, all integrals have limits of .

Applying the expectation yields a relatively simple expression,

The expectation is the autocorrelation of the noise process,

and assuming that the noise is stationary of order two, the autocorrelation is a function of the difference between the two times,

so that our expectation is given by

Our SNR denominator then becomes a bit more familiar,

Let’s express this in the frequency domain, realizing that the noise autocorrelation is the inverse Fourier transform of the noise spectral density

,

This basic relationship allows us to express the noise autocorrelation appearing in (16) as

and so the SNR denominator is

Now , and

is easy to evaluate too,

The denominator is then

We could have gotten there a little quicker by using results from other SPTK posts, but this was a good refresher, and a good warm-up for the numerator.

SNR Numerator

The numerator is a bit more complex than the denominator because it involves both the signal and the noise/interference. Let’s start by writing it out,

Now the signal, being known, is non-random, and let’s assume that the mean value of the noise/interference is zero for all ,

(Are you keeping track of the assumptions we’re making about ?) Armed with this information, we can expand the product in (24) and apply some of the expectations,

The second and third terms are zero due to our assumption of a zero-mean . The fourth term is identical to the denominator, which we know is given by (23). So our numerator work focuses on the first term, which we’ll call

.

Let’s recall Parseval’s relation, which for integrals says that the integral of a product of functions is equal to the integral of the product of their transforms,

Let’s apply this to and

in turn. First we need to put the integral into the proper

form:

which means we need the Fourier transform of and of

. The former is easy:

. The latter requires some care,

If we perform a substitution for the variable of integration equal to

, we obtain

Now we have a frequency-domain expression for ,

The term is closely related to

:

Finally, then, we have our term ,

which means we have a full frequency-domain expression for the SNR ,

The Matched Filter and the Maximum SNR

The task now is to find the particular that maximizes the SNR

expressed in (40). Often this kind of maximization involving integrals is difficult and solution techniques are complex. But here we have a bit of a shortcut: the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality.

First, notice that the second term in (40) cannot be negative, so that maximizing can be done by maximizing that term itself. Our optimization problem is then

Here is where the inequality comes to our rescue. The general form of the inequality (for integrals) is

with equality achieved when is proportional to

(

).

Let’s reexpress the quotient to make application of the inequality fruitful. In particular, reexpress the numerator so that after application of the inequality, the denominator cancels. We have the reexpression

provided that is never equal to zero (remember?).

Now we can identify and

in (42):

Applying the inequality is now straightforward,

with equality when

or

which is the matched filter.

It is easy to compute the maximum value of the SNR as

In the following, we’ll simplify our development and take the proportionality constant to be unity. So the general matched filter–the linear time-invariant system that maximizes output SNR for the detection of a known (non-random) signal in random stationary noise is given by

The matched filter is matched to the known signal because of the numerator of

–the input frequency components corresponding to those of the signal

are weighted by the strengths of those components–stronger parts of

count more.

The matched filter is also matched to the noise/interference through the denominator of –for those frequency components of the noise that are strong, the filter magnitude is small, and for noise frequency components that are weak, the filter magnitude is large. This effectively suppresses the stronger aspects of the noise, and is similar to the concept of spectral whitening we have encountered previously.

To find an explicit expression for the matched-filter impulse-response function , we’d need to inverse Fourier transform

in (51). We could try to invoke the convolution theorem, identifying the two transforms in the product as

and

, but we’d make little progress toward an enlightening expression. We could also try different choices for

, and that would probably be fruitful in proportion to the realism and utility of the particular choices.

We can also consider the common case of white Gaussian noise, where , a constant over all frequencies. In this case, the matched-filter transfer function is given by

In this case, we can easily perform the inverse transform,

The matched-filter impulse response for known signal is the conjugated and time-reversed signal itself.

Recalling the expression for the filter output , we have the following sequence of equations that show the connection of matched-filtering to correlation,

Neglecting the noise component of leads to

which is recognized as (proportional to) the autocorrelation of the signal evaluated at lag (delay)

. Therefore, matched filtering is equivalent to correlation in the white-noise case.

Degradation of “Known”

If your knowledge of the signal is imperfect, or if the transmitted signal undergoes a distortion or transformation that significantly changes it, then the impulse response of the matched filter will not actually be matched to the signal in the data. I stress that this can be the case even if your knowledge of the signal as it exits its transmit antenna is perfect. The propagation channel and your receiving equipment can both impart significant distortion or mathematical changes to the signal in the data you actually process. Let’s look at a couple examples.

Frequency Offset

A frequency offset (or carrier-frequency offset, CFO) occurs when a signal is received but is not perfectly downconverted to zero frequency. The matched filter assumes that you have, indeed, perfectly downconverted your signal, and so there is a mismatch. In terms of the matched-filter output (61), which neglects the noise term, we have the actual filter output of

which looks like the non-conjugate cyclic autocorrelation for . However, the CFO

is typically small relative to the smallest cycle frequency for

, so that this output is simply a degraded version of the desired matched-filter output. We’ll see a numerical example below.

To compensate, you could multiply the processed data by a complex sine wave, compute the matched-filter maximum, and repeat for a set of densely spaced sine-wave frequencies. Presumably the sine-wave frequency in this search grid that is closest to the actual unknown CFO would yield a maximum near the ideal matched-filter output. However, this extra brute-force CFO-compensation search will be more computationally expensive than a simple application of the matched filter, rendering it less attractive as a detection method.

Sampling-Rate Offset

The mathematics of the matched filter are presented in continuous time in this post, but when we apply a matched filter–or any filter–we are most often working in discrete time. A sampling-rate offset happens when you ask a system to provide samples at rate , but the samples are actually produced at a different rate

.

Instead of obtaining the sampled signal we obtain

. Suppose we warp the time axis to obtain

and then sample at sample rate

. Then we’d obtain samples

which are equal to

. Therefore, in continuous time, the sampling-rate offset is represented by a time-warped signal. Our matched-filter expression (61) becomes

For values of that are not close to unity, you can see that this new cross correlation will be smaller than the desired correlation in (61). A numerical example is shown below.

Linear Distortion

If the signal undergoes significant linear distortion en route to the receiver, or in the receiver, the known signal component is no longer fully known unless the impulse response for the distortive channel is also known. That is, if the channel has impulse-response function , then the received signal is

If we use the matched filter for to detect this distorted signal, the filter is not actually matched to the distorted signal, and is therefore no longer optimal. The decrease in the matched-filter peak will depend on the details of the distortion impulse-response function. A numerical example is provided below.

Examples

Let’s illustrate the power and the weaknesses of the matched-filter detector using signals of interest to us here at the CSP Blog. We start with broadcast TV.

ATSC DTV

The 8VSB/16VSB version of the North American broadcast digital television signal has significant built-in reception aids. It features a pilot tone at the left edge of its band, which accounts for about 10% of the total signal power, and also a periodically repeated known (to all DTV receivers) synchronization sequence (My Papers [16]). The sequence is 832 symbols long and repeats every 24 ms.

We can illustrate matched filtering by constructing the matched-filter impulse response from the modulated repeated sequence and then convolving that impulse response with a lengthy version of the signal, which contains several instances of the sequence. The result is shown in Figure 1, where the prominent matched-filter peaks are indeed separated by 24 ms. The action of the matched filter here can inform the receiver about exactly when each instance of the sequence appears. The receiver can then use the extracted sequences for timing recovery or channel estimation, if the propagation channel is not so severe that it erases the matched-filter peaks (see below).

The existence of a small carrier-frequency offset (CFO) in the received data that is not accounted for in the matched-filter impulse response can severely degrade the matched-filter output. Figure 2 shows the PSD and matched-filter output for a received signal that has a CFO of about 0.0015. Visually compare the PSDs in Figures 1 and 2–this is a small CFO. However, the peaks have vanished, indicating that the match between the normal matched-filter impulse response and the actual received signal is poor. In the radar-signal context, such CFOs are actually caused by the Doppler effect, and estimating them is the key to estimating the relative velocity between the radar and the target. But usually in communications, such CFOs are a nuisance.

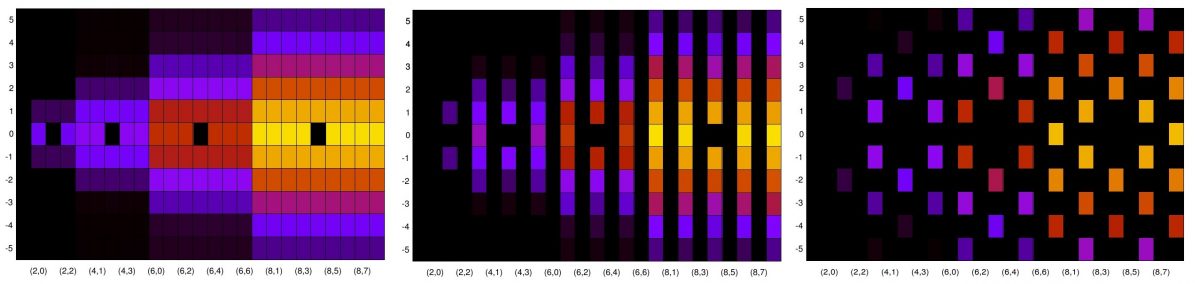

Next consider the case in which the receiver’s analog-to-digital converter delivers a sampling rate that is not as commanded. This is typically referred to as a sampling-rate offset (SRO). Figure 3 shows the PSD and matched-filter output for a signal with a non-zero SRO. To be clear, as in the nominal and CFO cases above, the matched-filter impulse response is for the ideal signal. Here the actual sampling rate is 101/100 times the desired rate.

Finally, consider the case where a frequency-selective propagation channel exists between the ATSC DTV transmitter and the receiver. This is common–see my post on ATSC DTV for more real-world examples. Figure 4 shows the filtered signal and the corresponding matched-filter output.

A Sine Wave

This example will be somewhat tangential–I attempt to relate the matched-filtering concept to more general estimation ideas.

Consider the problem of estimating the frequency of a noisy sine wave with unknown complex amplitude , with

, and unknown frequency

,

Assume that we have some samples of , and that the magnitude, frequency, and phase parameters are real-valued. A classic paper from the 70s (The Literature [R201]) shows that an optimal estimator of

can be had by maximizing the (square-root of the) periodogram,

where again, I remind you, the spectral frequency is continuous (a real number).

To implement (69) would require a search over all real numbers, or perhaps over all real numbers in some bounded set such as with

real numbers. Not gonna happen!

But notice that the sum in (69) is essentially a matched filter for a sine wave with frequency (proof left as an exercise for the reader). So the optimal estimator (according to [R201]) consists of trying all possible sine-wave matched filters, and picking as the frequency estimate the frequency that produces the largest matched-filter output. Satisfying!

Now the sum in (69) is just the discrete-time continuous-frequency Fourier transform. When restricted to an evenly spaced set of frequencies, it becomes the discrete Fourier transform, and the DFT, in turn, is efficiently computed by the fast Fourier transform (FFT). This is fast, and indeed remains optimal if the sine-wave frequency happens to be equal to one of the FFT frequencies. But that is almost never the case.

The full estimator in [R201] starts with maximizing the DFT/FFT version of (69), which produces an initial coarse estimate constrained to be one of the FFT frequencies. Then a restricted-domain brute-force fine search is used, based on restricting the frequencies used in (69) to lie near the coarse estimate.

Linear FM Pulsed Radar

In pulsed radar systems, the radar transmitter sends out a sequence of high-power pulses with significant gaps between them. During the gaps, the radar receiver can listen for echoes.

A typical pulse is the linear FM pulse, commonly called a chirp. The radar signal itself can be modeled as a carrier-modulated pulse train,

where each pulse is a chirp,

In such radar signals, the pulses are repeated every seconds, which is the pulse-repetition interval, and have widths

seconds, with

.

Because the radar’s target is typically quite far away, and the radar signal has to travel to and from the target, the reflected radar echo at the receiver is usually quite weak. But here comes the power of the matched filter! The chirp has a very narrow autocorrelation function, and you can control the pulse width as well as the rate at which the chirp frequency varies (through ). Using the known transmitted chirp, we see in Figure 5 that the echoes are easily detected even when the radar pulses are buried in receiver noise.

Significance of the Matched Filter in CSP

I’d like to emphasize the connection between matched filtering and correlation (see (61)). Once you realize that filtering is strongly connected to cross correlation, you begin to interpret correlation as filtering. And correlation is king in CSP–the autocorrelation, the cyclic autocorrelation, the power spectrum, and spectral correlation are all forms of correlation, and so we can think of them as filtering.

More specifically, consider CSP algorithms such as the single-cycle detector. Such detectors can be derived by posing optimization problems, such as ‘find the quadratic functional of a signal that produces the maximum-SNR sine wave with frequency .’ Recall one expression for the cycle detector is given by

where is an estimate of the spectral correlation function for

, and

is the theoretical (known!) spectral correlation function for

. It is reasonable to model the estimate as

where is measurement noise. Then the integral inside the cycle detector is

which looks a lot like a frequency-domain matched filter for a known signal .

A maximum-likelihood analysis of a weak-signal two-sensor detector in My Papers [4] reveals a plethora of matched-filter-like structures all working together to perform detection:

Template-matching styles of image or signal classification can also be interpreted as correlations and matched filtering. For example, the spectral-correlation-matching and cyclic-cumulant-matching subalgorithms in My Papers [25,26,28] have at their heart a correlation between a theoretical probabilistic parameter and a noisy measurement thereof.

As usual, comments, questions, and my errors are welcome in the Comments section below.

Previous SPTK Post: The Characteristic Function Next SPTK Post: Wavelets

Another outstanding article Chad. Thank you!

Equation (26) line 3 is missing inside the double integral.

inside the double integral.

In your ATSC example, you chose strictly greater than

strictly greater than  basically through periodization (every 24ms). What can we say about the performance of the matched filter when

basically through periodization (every 24ms). What can we say about the performance of the matched filter when  =

=  versus

versus  ?

?

Regards,

Mansoor

I think the peak SNR represented by (50) does not change if , which condition just means that the known signal is completely contained in the processed data, and that the processed data is exactly as long as the known signal.

, which condition just means that the known signal is completely contained in the processed data, and that the processed data is exactly as long as the known signal.

When , as you note, you get the situation I’ve depicted in the ATSC examples: lots of low-magnitude matched-filter outputs and peaks wherever the known signal appears.

, as you note, you get the situation I’ve depicted in the ATSC examples: lots of low-magnitude matched-filter outputs and peaks wherever the known signal appears.

For $latex T_d < T$, only a portion of the known signal can be contained in the processed data of length $latex T_d$. In this case, I think you can consider that the matched filter for the full known signal is equal to the matched filter for the partial known signal concatenated with an irrelevant sequence, which I believe renders it suboptimal, strictly speaking. As an example, if the ATSC DTV signal is delayed so that the first instance of the known signal component is truncated, the output of the matched filter (matched to the full signal component) is decreased in magnitude equal to the fraction of the known signal that does not appear. Here only half of the known component appears at the very beginning of the data record:

Thanks For a very useful and well-written article! I am looking for ways to use matched filtering to reveal musical note sequences. This would be a case of receiving-only rather than transmitting-then-receive-echo. Is there a way to use matched filtering to determine the duration of a musical signal such as the note of a flute, using a matched filter based upon the same flute note? I hope to report experiments soon with synthetisized sounds.

Welcome to the CSP Blog Charles! Thanks for the question.

The answer is yes, provided the note is a periodic or near-periodic signal. I believe musical notes are not pure tones (a single sine wave), but are essentially periodic signals composed of multiple harmonically related sine waves (see Fourier series post).

In such cases, if the matched filter is created using a relatively short-duration segment of the note, and the note in the data persists for a time interval greater than the matched-filter length, then the matched-filter output will assume a large value over the duration of the note. Here is a simplified example using a pure tone, but the concept is valid for any periodic (or near periodic) signal:

If you send me some of your musical note data, I can quickly try it out for you.