Previous SPTK Post: The Z Transform Next SPTK Post: IQ Data

Linear shift-invariant systems are often called digital filters when they are designed objects as opposed to found objects, which are models, really, of systems occurring in the natural world. A basic goal of digital filtering is to perform the same kind of function as does an analog filter, but it is used after sampling rather than before. In some cases, the digitally filtered signal is then converted to an analog signal. These ideas are illustrated in Figure 1.

What is a good starting point for a general look at digital filters? Analog filters are typically characterized by differential equations. As before we can start with these systems and discretize them to find general discrete-time equations relating linear shift-invariant system inputs to outputs. We will see something intuitively pleasing: the output at any sampling time is equal to the sum of linear combinations of the previous values of input and output.

Jump straight to the Significance of Digital Filters in CSP

General Digital Filters

A general linear th-order continuous-time system with input

and output

is described by the differential equation (see also the SPTK post on the Z transform)

where denotes the

th derivative with respect to time

, and the zeroth derivatives are equal to the signals themselves,

We know how to discretize if

is sufficiently small because we recall the definition of the derivative. So we have the approximation

but how can we discretize the higher-order derivatives? Let’s take a close look at the second derivative to get started. In continuous time, the derivative is closely approximated by

if is sufficiently small. The second derivative is then approximated by

The sampled version of contains samples of

at times

,

, and

. In general, the

th derivative of

will contain some combination of the values

, and the same is true for the sampled derivatives involving

. Therefore we can write the general

th-order difference equation that corresponds to the general

th-order differential equation as

It is customary to extract from the sum over

and normalize the equation by

to obtain the form

where the coefficients in (9) are not the same as those in (8) unless happened to be unity. This form, only slightly modified, is what MATLAB implements for you with its filter.m (see Figure 2).

For the special case for which for

we have

and the output at time is see to be a weighted sum of the previous

input values plus a weighted version of the current input value. This kind of digital filter is call non-recursive or finite-impulse response (FIR). The latter appellation is appropriate because the filter’s impulse response has a finite extent in time,

Since unless

, in which case it is equal to one, we have

A concrete example of a FIR filter is the moving-average filter.

We can diagram the FIR filter in several ways. In the first method, the successive delays are simply denoted by blocks containing the instruction “Delay “, as in Figure 3.

Another common way to diagram digital filters is to use the symbol to denote a delay by a single sample. This arises from the Z-transform delay theorem (The Z Transform equation (61)), summarized here as

The resulting diagrammed FIR filter is shown in Figure 4.

The visualization of the FIR filter in Figure 4 leads to an interpretation of the filter action in terms of tapping off the signal after each delay. The delays all appear in a straight line in the diagram, leading to an alternative name for the structure: a tapped-delay line.

When at least one and one

are nonzero, the filter is called recursive or infinite-impulse response (IIR). It is recursive because the current output depends on previous inputs and outputs, unlike the non-recursive FIR filter, which depends only on the current and previous inputs. The general IIR filter is diagrammed using Z-transform delay elements in Figure 5.

Let’s take a look at an IIR impulse response for a simple special case in which ,

for

,

, and

for

:

The output is equal to the impulse response function for the filter,

, when the input is an impulse function,

. Let’s step through a few values of

for this situation.

For general then, we see the pattern:

Since we assumed that and

,

will never be zero for any

. Therefore, the length (support) of

is indeed infinite.

We now have our basic digital-filter computational structures–FIR and IIR–and a strong connection between digital filters and analog systems that are governed by differential equations (for example, lumped-parameter electronic circuits and many mechanical systems). In this setting, the filter analysis problem is the determination of the transfer function and impulse-response function for a particular given filter. The filter synthesis problem is to choose the values of and

to achieve a structure that produces a given transfer function or impulse response.

Frequency Response for Digital Filters

Our discretized analog system resulted in the input-output relation given by

Does this represent a linear shift-invariant system? To check for linearity, we must compare the outputs for (1) inputs and

with (2) the output for

. For time-invariance, we have to compare the outputs for (1) input

with (2) input

. I encourage you to try this proof.

Another way to look at it is to simply compute the Z transform of (19) and see if it can be rewritten as , in which case we know that input

is related to output

by convolution in general.

Let’s proceed by assuming that (19) represents a linear shift-invariant system. Then we can confidently use our normal discrete-time linear-system tools and characterizations, such as impulse response, transfer function, and transforms.

The Z transform (one-sided here) is

Applying the transform to (19):

Since , this transform simplifies to

Rearranging this equation to find leads to

Therefore and

are indeed related by a convolution since

.

in (24) is called the discrete-time transfer function or the digital filter transfer function. It’s inverse Z transform is the discrete-time impulse response for the filter.

The digital filter frequency response is simply the transfer function evaluated on the unit circle in the plane, which means substitute

into (24),

The frequency response for a digital filter is periodic in frequency . This is simply due to the periodicity of the complex sine wave,

if , where

is any integer. This periodicity requirement is met with

. So, the frequency response of a digital filter is periodic with period equal to the sampling rate.

Examples

The Moving-Average Filter

We’ve encountered the moving-average filter before in the SPTK series of posts. Here we view it in the context of digital filters and also extend it by modulating the impulse response, which has profound implications for the frequency response.

The discrete-time moving-average filter is our general digital-filter structure with all of the feedback (recursive) coefficients and all of the non-recursive coefficients

are equal to some constant

. The input-output relationship is then

For example, if , then the filter can be interpreted as forming the average of the current input value together with the past

input values. The Z transform of

follows easily from the Z-transform delay theorem and the fact that the Z transform is linear. The frequency response is that Z transform evaluated at

. You can verify that the result is

This formula is, once again, an example of a geometric series. The generic series is

for which a simple formula for can be had by looking at the difference

,

which is valid provided . Using this formula with

leads to an expression for the frequency response

This can be simplfied by some algebra to reveal a sinc-like frequency response,

Why do I say “sinc-like” here? Consider large and small

, then for smallish

, the denominator

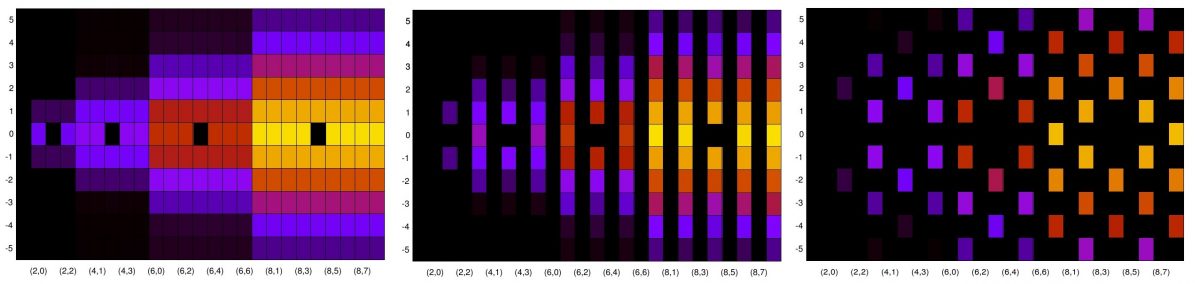

, and we get our sinc-like behavior. But let’s plot it in Figure 6 for several values of

and

to get a more accurate view of this frequency-response function.

Even without the ability to nearly effortlessly plot (33), we can get a good idea of its behavior with a little more math. For , we see that both the numerator and denominator of

in (33) are equal to zero, so we have the limiting form of

as

, which is undefined. However, we can use L’Hopital’s rule to evaluate the function at

. This requires that we differentiate the numerator and denominator and form the new quotient from those results

from which we easily see that as

. For our typical moving-average choice of

, this means that

. This is pleasing because it means that if your input is a constant (a sine wave with frequency equal to zero), then the filter simply passes the signal unchanged. In the case of a constant, the average is always equal to the constant.

Other values of the frequency response (33) can be had using pencil and paper if a numerical value is chosen for , such as

, and then frequencies are chosen to be “friendly” to easy

function evaluation, such as

.

Overall, we see that the moving-average filter is of the lowpass variety in that the frequency response is relatively large for small frequencies and relatively small for large frequencies

.

A Modulated Moving-Average Filter

The impulse-response function for the moving-average filter, a FIR filter, is particularly easy to compute by simply replacing the input with an impulse

,

Let’s modulate this filter by multiplying the normal moving-average impulse-response function (46) by a sequence of alternating and

values as in

What is the frequency-response (transfer) function for this modulated filter? As usual, we need to evaluate the Z transform of on the unit circle,

Preview: Modulating the impulse response by a sequence of alternating values shifts the filter’s transfer function by half the sampling rate. Let’s see exactly how that comes about.

Let’s reexpress the factor with an eye toward getting the sum into our usual geometric-series format, which is easily simplified:

Continuing on with the frequency response using this new expression for ,

where . Now we have the geometric series expression, and we can simplify,

The magnitude of the frequency response, , is given by (substituting back in

),

or , where

is the moving-average filter frequency response from (33). So the

modulated impulse response corresponds to a frequency-shifted version of the moving-average frequency response. This is illustrated by the various frequency-response plots for this first modulated moving-average filter in Figure 7.

A Second Modulated Moving-Average Filter

Let’s generalize this idea of modulating the impulse-response function by considering a final filter where the moving-average impulse response is multiplied by a complex sine wave with frequency

where . (Note that the previous example simply used

.) Once again, let’s find and plot the frequency response for this new filter.

The math is nearly identical to that we encountered for the moving-average and modulated-moving-average filters. The result is

This last filter has a complex-valued impulse response, unlike the previous two filters. This means that the frequency response will not necessarily be symmetric around . (Think of that first modulated filter. Multiplying by alternating

values is equivalent to both multiplying by a sine wave with frequency

and multiplying by a sine wave with frequency

.)

Plots of the frequency-response magnitude for this final version of the moving-average filter are shown in Figure 8. Notice that the filter is of the bandpass type. So we have shown that one can create lowpass, bandpass, and highpass filters using just the moving-average impulse response and simple multiplication by a sine wave. Now, how would you create a notch or bandstop filter here?

Comments on the Bandwidth of Digital Filters

Normalized Bandwidth, Normalized Frequencies

In this situation, the sampling increment is taken to be , and so the sampling frequency is

. The first zero of the moving-average frequency response (

in (33)) is then at

and so a reasonable measure of the filter’s bandwidth is .

Absolute Bandwidth, Absolute Frequencies

When we want to consider absolute, or physical, frequencies, we retain in all expressions for times and frequencies. So for our simple moving-average filter, the approximate bandwidth is

By choosing very large, say 1 MHz, we find that the filter bandwidth is

The response of the digital moving-average filter to an input sine wave with frequency kHz is

and the response to a sine-wave input with frequency kHz is

Normalized Digital-Filter Descriptions

For normalized descriptions of digital filters, where is implied by the employed notation, such as

we can perform all our calculations and design and convert to absolute frequencies whenever we wish by multiplying the normalized frequencies by the sampling rate and multiplying the normalized times by the sampling interval

.

A Continuous-Time Filtering Problem Solved with a Digital Filter

We’ve seen several examples of the frequency response for digital filters (practical discrete-time filters). We’ve seen a lowpass filter (the moving-average filter (33)), a highpass filter (the modulated moving-average filter (46)) , and a bandpass filter (the sine-wave-shifted moving-average filter (48)). The frequency responses are believable in that they are approximate versions of the continuous-time filter counterparts (but are periodic).

Now let’s try to show the big picture here by starting with a continuous-time filtering problem and determining the digital filter that can be used to solve that problem. That is, we combine elements of continuous- and discrete-time signal processing in one example.

Suppose we want to build a continuous-time system that performs filtering that is lowpass in nature and has a 3-dB bandwidth of 10 kHz. One starting point for this system is to reach back to our practical filters and look at a first-order system described by the simple first-order differential equation

The specified 3-dB cutoff frequency for this system is radians. This system has transfer function

and impulse-response function

For the discrete-time system component of our overall system, we want the impulse response to equal samples of the continuous-time impulse response. Let’s call the discrete-time impulse response . The situation is illustrated in Figure 9.

In this setup, and

are related by

, and

and

are related by

. We want

which implies

What is the frequency response for this digital filter? To find it, we should evaluate the Z transform of on the unit circle, as usual:

This region of convergence for the transform, , includes the unit circle provided that

and

, which is true for our example by definition. That is, we are free to constrain

to be positive, and the sampling increment is positive by definition.

We arrive at

Let’s diagram the system and plot the frequency response . From the definition of the discrete-time transfer function, we have

or

The block diagram for this system is shown in Figure 10. Note that the gains in the triangular multiplier blocks depend on the desired continuous-time time constant and the sampling increment

.

Notice that the digital-filter transfer function is periodic with period (as always). The squared magnitude of the transfer function is

The squared magnitude is plotted in decibels in Figure 11 (the figure plots ).

The Significance of Digital Filters in CSP

A prominent digital filter used in CSP is not a time-domain filter, but is a filter that is applied to discrete frequencies in the frequency-smoothing method (FSM) of power-spectrum and spectral-correlation estimation. In the FSM method, the sampled-frequency cyclic periodogram is convolved with a finite-impulse-response (FIR) moving-average filter in order to quell its inherent randomness and allow the estimator to approach the underlying ideal spectral correlation function.

Time-domain FIR filters are good models for real-world multipath propagation channels, and the effects of real-world propagation channels are always of interest in CSP because they affect the observable cyclostationary features of a transmitted signal.

Time-domain FIR filters are central to discrete-time discrete-frequency frequency-shift (FRESH) filters that can be used for single-sensor separation of two or more cochannel and contemporaneous cyclostationary signals.

Digital filters are central to polyphase filterbanks, as we’ve discussed previously, and such filterbanks are crucial efficient structures that enable advanced CSP techniques such as tunneling.

Recursive (infinite-impulse-response) digital filters are used much less in CSP (at least by me), but sometimes are useful in efficiently implementing long-tail “forgetting factor” kinds of filters, whose outputs mostly reflect the most recent inputs but that do not completely discount inputs from the distant past.

Let the CSP Blog readers know if you use digital filters in your CSP work in the Comments. And, as always, feel free to point out any errors you find in this post.

Previous SPTK Post: The Z Transform Next SPTK Post: IQ Data