Previous SPTK Post: Digital Filters Next SPTK Post: The Characteristic Function

Let’s really get into the mathematical details of “IQ data,” a phrase that appears in many CSP Blog posts and an awful lot of machine-learning papers on modulation recognition. Just what are “I” and “Q” anyway?

Jump straight to the Significance of IQ Data in CSP

Bandpass Signals and Their Complex Representation

To set the stage, we review the idea of a bandpass signal which, in the context of manmade radio-frequency signals, means modulating a lowpass message or sensing signal. ‘Modulating’ here simply means multiplying by a sine wave, because we know from Fourier analysis that multiplying a signal by a sine wave (real-valued or complex-valued) results in a signal

whose Fourier transform is a frequency-shifted version of

.

Suppose we have some real-valued message signal, such as a voltage that is proportional to a music or speech (acoustic) signal, our and we want to transmit those samples using a radio-frequency signal near

Hertz. We can do that by modulating

to create the transmitted signal

,

If , meaning

is the Fourier transform of

, then we can use our Fourier-transform knowledge to obtain an expression for

,

This frequency-translation process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Why would we want to move the signal’s transform from near zero frequency to some much higher frequency ? The reason is radio-wave propagation. Electromagnetic waves will propagate through different media–air, water, free space, the Earth, a metal conductor, etc.–differently. Some media may absorb much of the wave’s energy over short wave-traveling distances, meaning that the wave must have very high power (relative to what we can generate using our electronics) to permit traveling the required distance.

The propagation distance for a given power level and propagation media depends on the frequency of the wave. Therefore, if we wish to propagate our information across time and space to our receiver, we need to select a frequency that permits low-loss propagation through the chosen media for the distances of interest, which may vary from a few meters for a personal-area network to many kilometers for a wide-area network to tens of thousands of kilometers for geostationary satellites. Typical media (for example, the Earth’s atmosphere or the ionosphere) will require much higher frequencies for good propagation than the native frequencies of the signal to be transmitted.

In addition to propagation power loss, the other aspects of propagation must be considered when choosing a suitable frequency band for transmission: refraction (redirection), diffraction (bending), and reflection (bouncing).

So the dilemma in RF transmission and reception is that we are forced to use high frequencies for transmission, but our messages are inherently low frequency. We need mathematical tools to understand the relationships between the original (“baseband”) signal and the transmitted (“RF”) signal. That is where IQ comes in.

Applying an arbitrary linear time-invariant filter to the transmitted (RF) signal leads to a distortion of the spectral shape seen for the baseband signal, as illustrated in Figure 2. We now have a bandpass real-valued signal where the PSD for positive frequencies is no longer necessarily symmetrical around .

Our general interest here, then, is in signals like in Figure 2, where the power of the signal is concentrated around the carrier frequency

, which is very far from zero relative to the bandwidth of the signal,

.

Inphase and Quadrature Components

Suppose we have some bandpass signal with Fourier transform

shown in Figure 3. The function (signal)

is a model for the actual transmitted waveform–no complex numbers are involved. We know that this signal is a real-valued sine wave with time-varying amplitude and/or phase,

We will eventually want to sample such signals and manipulate their mathematical expressions as they pass through various systems such as filters. From the basic results of the sampling theorem, we’d have to sample such signals at a rate at a minimum rate of twice the largest frequency component of the signal, or , which could be a very large number indeed if the carrier frequency is something like 2.5 GHz (the WiFi/Bluetooth ISM band).

Can we represent in a more convenient way? Let’s take a look at its structure.

First, we use a trigonometric identity to reexpress the compact (3) using two sine waves instead of one,

which leads to

We see that the bandpass signal is the sum of two real-valued sine waves, and

, with time-varying amplitudes. Two sine waves are said to be in quadrature if their phases differ by ninety degrees (

radians), such as the two involved sine waves here. This leads to identification of the in-phase and quadrature components of the bandpass signal,

The in-phase component is often denoted simply by “I” and the quadrature component by “Q.” So now you know the origin of “IQ data.” (I’m using instead of

because I’m using

to mean the square root of negative one, as usual on the CSP Blog.)

The Complex Envelope

Let’s now take a look at by taking the Fourier transform of our IQ representation (6) (and here is where lots of our SPTK tools pay off),

where

Grouping terms that are spectrally similar we obtain the alternate expression for the bandpass-signal transform given by

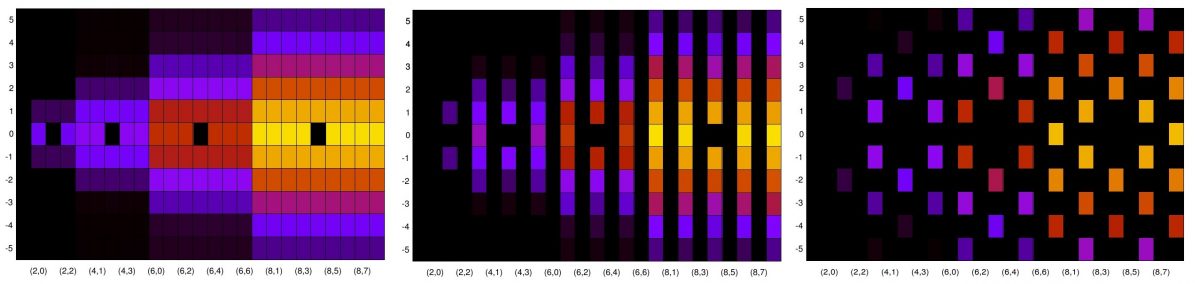

which is illustrated in Figure 4.

If we know and

, we can construct the real-valued signal

from

. In this sense, the set

is a representation of

(of course, we need to know

too).

It must be the case that the positive-frequency portion of is equal to the sum of the in-phase and quadrature transforms,

and

But we can get the negative frequency portion of the signal (15) from the positive-frequency portion (14). Consider the complex-envelope signal

Recalling the definitions of and

,

and noting that the inverse Fourier transform of is given by

we have

or

Looking back at the bandpass signal , we can see the relationship between that signal and the complex envelope,

So the real-valued (actual) RF signal is represented by a fictitious complex-valued baseband signal

multiplied by a complex-valued sine wave.

The Fourier relationships between the complex envelope and RF signal are also of interest in the context of computing the complex envelope from a real signal,

Now, our previous work on the Fourier transform and frequency shifting (modulation) leads to the transform pair

But what is the transform of ? Let’s take it step by step,

Putting it all together, we have the transform of the bandpass signal in terms of transforms of the complex envelope,

The real-valued bandpass (RF) signal, the analytic signal, and the complex envelope are illustrated in Figure 5.

Working with the Complex Envelope

The complex envelope is convenient to work with because it has low bandwidth relative to the bandpass (RF) signal, and so we can sample it at a much lower sample rate and still preserve all the signal’s information. The downside is that now we have to work with complex signals and complex numbers.

We can always form a lowpass model of the signal (complex envelope) and a propagation channel (frequency shift it by ) so that the complex data we work with faithfully represents the action of the real channel on the real signal. Suppose the RF (bandpass) signal experiences a channel

(see Figure 2). Then the output of the channel is

,

where

A practical circuit to extract the in-phase and quadrature components would consist of two parallel branches. The input to each branch is the RF signal voltage. The upper branch multiplies the RF signal by a sine wave and the lower branch multiplies the RF signal by

. It is important that these two sine waves are in quadrature–they must have the same frequency and differ in phase by

radians or 90 degrees. The output of the upper branch is the continuous-time in-phase component

and the output of the lower branch is the continuous-time quadrature component

. These two continuous-time signals can then be synchronously sampled at a rate appropriate to the bandwidth of the signal (or scene).

When the frequency used in the complex-envelope extraction process is not exactly equal to the center frequency

of the signal, the obtained complex envelope will not be centered at zero frequency. Instead, it will be centered the difference between the two frequencies,

. Often this is a small number compared to the bandwidth

and it is called the carrier-frequency offset (CFO), which we have encountered many times on the CSP Blog.

Regardless of whether or not, the obtained complex-valued in-phase and quadrature data is referred to as either the complex envelope or the complex-baseband signal.

The Significance of IQ Data in CSP

In CSP, we prefer to work with the low-sampling-rate complex-baseband data because the required sampling rate is on the order of the bandwidth rather than on the order of the carrier frequency

. That way, a processing data block of length

samples covers many more seconds, which means it covers many more instances of the various involved random variables that make up the signal. And all our CSP work involves the ability to average, in various ways, over those random-variable instances.

However, the choice to use complex-valued data has consequences. The main consequence is that we must use multiple versions of standard moments and cumulants that take into account the different ways one can choose to conjugate or not conjugate factors in a delay product like

This is explained in detail in the post on conjugation configurations.

Previous SPTK Post: Digital Filters Next SPTK Post: The Characteristic Function

Hello Chad!

it’s been a while since we last communicated. My hardware implementation project is progressing well, and I’m considering next steps. Could you advise if the STFT algorithm has any significant applications in the field of cyclostationary analysis? I’m currently thinking about using STFT in the customozed feature extraction layer to see its effectiveness.

Best Regards,

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is associated with several kinds of time-frequency analysis functions, and the names of those functions seem to have been evolving and changing lately with the infusion of machine learning into RF signal analysis spaces.

The basic STFT is a complex-valued matrix, and you can go back, losslessly, to the original time-domain data. So all magnitude and phase information relating to the signal(s) in the transformed data are preserved.

The STFT matrix can be converted to a matrix of periodograms by computing the squared magnitude of each row and multiplying each row by the reciprocal of the transform length after that. Further, the spectrogram can then be computed from that matrix by convolving each row with a pulse-like function (e.g., a rectangle). That is the conventional (old?) use of “spectrogram”: a stacked set of power spectrum estimates (not complex-valued Fourier transforms, not the tranform magnitude, not the periodogram), where each power spectrum estimate corresponds to a different temporal window applied to the long input signal. Even wikipedia gets some of this wrong, conflating the squared-magnitude with the power spectrum (the squared magnitude isn’t even the periodogram, quite):

In CSP, the spectrogram isn’t all that useful (that is just my opinion, not a fact), but a sequence of cyclic periodograms taken over time in a sliding-block style is intimately related to the time smoothing method of spectral correlation estimation.

In many machine-learning papers on modulation recognition, the spectrogram is used as an input to a CNN, or the input is the magnitude of the STFT, and performance isn’t good for digital signals like QAM. But more recently, researchers are using the complex-valued STFT as a complex-valued (two-channel) image in more-or less conventional image-processing CNN structures, which is an improvement over the magnitude-only STFT and spectrogram approaches, since the signals have significant phase differences. But this approach is essentially the same as using the I/Q data itself as an input, which we know has serious performance and generalization problems when the neural network model is of the image-recognition type.

Chad,

Great article covering sampling of bandpass signals. For those interested in an alternative direct bandpass sampling scheme (meaning no downconversion to baseband prior to sampling), my colleague and I have proposed just that in this IEEE paper:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9905989/citations?tabFilter=papers#citations

Cheers,

Mansoor

Thanks Mansoor!

The post is the basic math behind the “what” of I/Q samples. Mansoor provides a link to a cutting-edge efficient “how” to get I/Q samples. You can think of it as an alternative to the method I sketched starting just after (37), where I say “A practical circuit …”.