Previous SPTK Post: LTI Systems Next SPTK Post: Interconnection of LTI Systems

We continue our progression of Signal-Processing ToolKit posts by looking at the frequency-domain behavior of linear time-invariant (LTI) systems. In the previous post, we established that the time-domain output of an LTI system is completely determined by the input and by the response of the system to an impulse input applied at time zero. This response is called the impulse response and is typically denoted by .

[Jump straight to ‘Significance of Frequency Response in CSP’ below.]

The impulse response is useful and mathematically elegant, but looking at it as a graph doesn’t provide a lot of insight into the particular linear system under study. At least for me, anyway. For example, here are several impulse responses graphed on a single set of axes:

It is difficult to view the magnitude and phase of the impulse response and quickly surmise how input signals are transformed into output signals, even for the simple (but important) case of inputs that are sinusoidal. So let’s take a close look at just how a linear time-invariant system transforms a sine-wave input.

LTI Input-Output Relationship for Sine-Wave Input in Continuous Time

Suppose our input signal is ,

where is the real-valued amplitude,

is the frequency, and

is the phase parameter. Now recall that the output

of any linear time-invariant system is the convolution of the input

and the impulse-response function

,

Using our sine-wave in (1), we can calculate the output in the following way

More compactly, we use the symbol to denote the Fourier transform of

to obtain the input-output relationship

or

We interpret this result to mean that an LTI system passes a sine-wave input to the output after scaling it by the complex number , where

is the frequency of the input sine wave and

is the Fourier transform of the impulse response. That is, “LTI System” implies “Sine-wave In, Sine-wave Out.” Linear systems do not create new frequency components, they can only scale each frequency component at the input to produce a contribution to the output.

The number is the response to the sinusoidal input with frequency

, and so the function

describes the full frequency response for all possible sine-wave inputs.

Now recall that all energy signals can be represented by their Fourier transform (and some power signals too),

So we can guess that the response to an arbitrary input will consist of the sum of the weighted sine-wave components of the input signal, where each sine-wave component with frequency is weighted by the complex number

. We’ll show this is in fact true later in the post.

I note in passing that this analysis of linear time-invariant systems’ input-output behavior can be viewed as deriving the Fourier transform (see (5)).

LTI Input-Output Relationship for Sine-Wave Input in Discrete Time

Suppose we input a discrete-time sine wave to a linear shift-invariant system with impulse response ,

The output is the input convolved with the impulse response

which is the same result we found in continuous time. If is causal, and has only a finite number of non-zero values (it is an FIR filter), then

for

and

, and we have

We can sample this function of frequency over the interval

times by using the frequencies

:

which we recognize as the discrete Fourier transform.

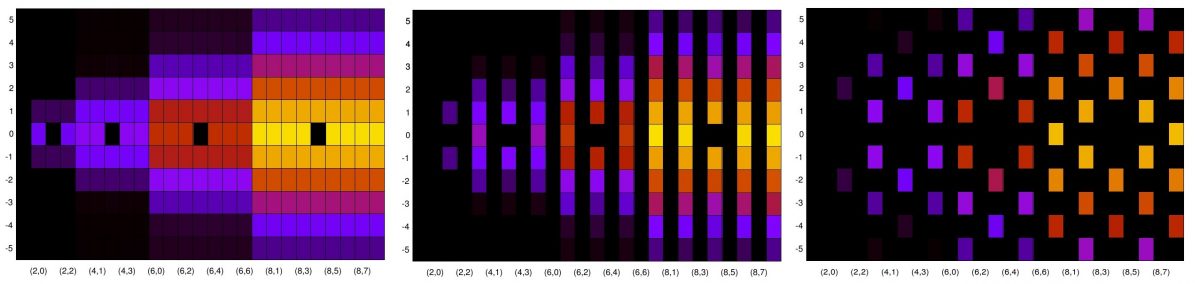

Returning to the example of the three impulse responses in Figure 1, if we instead compute and plot the frequency responses, we obtain the graphs in Figure 2:

Focusing on the upper plot, which shows the magnitude of the frequency response for each linear time-invariant system (filter), we see that these three filters are piecewise constant. They are either zero or, on some intervals, they are equal to a non-zero constant. For any frequency

for which the frequency response function

is zero, an input sine wave with frequency

will produce a zero-valued output. That is, the sine-wave will be blocked and will not appear at the output (more mathematically, it appears at the output with zero amplitude).

Readers having some familiarity with filter terminology will recognize that the three filters in Figure 2 are ideal filters, and that is a low-pass filter,

is a bandpass filter, and

is a high-pass filter.

General Input-Output Relationship for LTI Systems

Now let’s apply the Fourier transform to the time-domain input-output relationship for LTI systems, which is the convolution integral. That is, we have the output for the input

of an LTI system with impulse-response function

,

We want to find the Fourier transform of . Can you guess what it will be in terms of the Fourier transforms of

and

? Let’s use the symbol

to denote the Fourier transform operator:

Let’s go through the exercise.

or

So, a convolution in the time domain is a multiplication in the frequency domain. A truly difficult-to-evaluate convolution may be quite easy in the frequency domain, provided the individual transforms and

can be found. Moreover, this basic frequency-domain input-output characterization is consistent with our original encounter with

as the complex number that scales the amplitude of an input sine wave with frequency

:

describes the scaling of each and every sine-wave component of the input.

Because describes how the linear time-invariant system transfers an arbitrary frequency-domain input to its frequency-domain output,

is also called the transfer function of the filter.

***

Let’s circle back to the meaning of the impulse response. Suppose we have an input described by the Fourier transform

that is, the transform of the input is equal to one for all frequencies

. Then our frequency-domain input-output relation reduces to

which means the output of the system is equal to the transfer function. But what time-domain has

for all

? Well, we already encountered this signal, which is the impulse function

So, if we manufacture an impulse function, and apply it to our system, we will obtain the impulse response by definition, and this corresponds to an input that simultaneously applies all possible unit-magnitude sine waves to the system. This explains the origin of the formerly common behavior called ‘kicking the tires.’ When inspecting a car, it is stereotypical that the inspector (customer) will give a sharp kick to a tire to see what happens with the car. That is, if something falls off, the tire moves around, or some unsettling noises emit from under the hood. The inspector here is simultaneously applying all sinusoidal forcing functions to the mechanical system, hoping to observe a tell-tale resonance.

Significance of the Frequency Response in CSP

The frequency response, or transfer function, of a linear time-invariant system comes up in various places throughout the theory of CSP. The most prominent example is when we want to find the spectral correlation function for a random signal that has passed through an LTI system: what is the spectral correlation function for the output as a function of the spectral correlation of the input signal and the transfer function of the filter? As a concrete example, the input signal might be a communication signal and the LTI system might be a multipath propagation channel. We’ve already shown that the result (for the non-conjugate SCF) is

See the post on signal processing operations in CSP for more details.

Previous SPTK Post: LTI Systems Next SPTK Post: Interconnection of LTI Systems

Hi Chad,

There’s a very nice interpretation to equation (34). It might be somewhere on your site, but I couldn’t find it, so I’m sorry if I repeat it here.

In classic SP, the spectral density at frequency f0 is defined as the average power of a signal through a (narrow) BPF around f0. Then, by using the definition of the autocorrelation function and decomposing the signal into a sum of signals through BPFs, it is shown that the autocorrelation function is actually the inverse Fourier transform of the spectral density. In other words – we define both the correlation function and the spectral density independently and then show they are related by the Fourier transform.

There’s also the converse approach:

We define only the autocorrelation function and look at a signal through an LTI system.

It’s easy to show that:

where x is the input, y is the output, h is the impulse response of the LTI system and is the time-flip + conjugate operator.

is the time-flip + conjugate operator.

We then *define* the spectrum as the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation function.

When we transform the output of the LTI system we get the non-cyclic case of equation (34):

Notice the average power of x(t) is given by:

So this gives an interpretation to the definition by Fourier transform.

If we take h(t) as a (narrow) BPF around f0, we’ll get Sx(f0). This means Sx is the spectral power density!

Similarly, for CSP, we can approach in two ways:

1. Define the cyclic correlation function and independently define the spectral correlation (as correlation between the outputs of two BPFs). Then we show their Fourier relation.

2. alternatively, we can define (just) the cyclic correlation function and then look at the cyclic correlation of the outputs of two LTI systems. If we pass x1 through h1 (to get the output y1) and x2 through h2 (to get y2) then it is easy to show that

Like in the power correlation case, we now *define* the spectral correlation function as the Fourier transform of the cyclic correlation to get:

Similar to the power case, when we look at the cyclic correlation of the outputs:

We look at the case where H1 and H2 are narrow BPF around and

and  respectively. This shows us that:

respectively. This shows us that:

In other words – is the correlation of the outputs through the narrow BPFs.

is the correlation of the outputs through the narrow BPFs.

Hey Roee! Thanks much for this comment, which I believe will be valuable for many many readers.

I think I agree with all of it except toward the end–that final equation. If is an ideal filter centered at

is an ideal filter centered at  with unit height and width

with unit height and width  ,

,  is an ideal filter centered at

is an ideal filter centered at  with unit height and width

with unit height and width  , and the cross spectral correlation function

, and the cross spectral correlation function  is “approximately constant” in an interval with width

is “approximately constant” in an interval with width  centered at

centered at  , then the right side of the penultimate equation is closely approximated by

, then the right side of the penultimate equation is closely approximated by

So there is a missing scaling factor in that last equation.

Agree?

See also the post on signal-processing operations and CSP for related equations involving higher-order cumulants and linear time-invariant systems.

Agreed!

Which makes sense unit-wise, since the spectral correlation is a density function, i.e. per Hz

Yes! I was hoping you’d say that. That mismatch in units in that last equation of your comment caught my eye immediately. “Unit Analysis,” also known as “Dimensional Analysis” is used by physicists, but can also be useful for us signal-processing types.