Previous SPTK Post: I and Q Next SPTK Post: The Matched Filter

Let’s return to the probability section of the Signal Processing ToolKit posts with a look at the characteristic function, which is the Fourier transform of the probability density function. We will see it has a deep connection to the central mathematical entities of CSP, which are moments and cumulants.

Jump straight to the Significance of the Characteristic Function in CSP.

Basic Definitions

The characteristic function for a real-valued random variable is the expected value of the function

. The variable

is a dummy variable; it has no intrinsic physical meaning. Recalling that the expected value of a function of a random variable is the integral of the product of that function and the probability density function for the variable, we can write the definition mathematically

Reexpressing this in a more familiar form leads to a Fourier-transform-like expression

If

are a Fourier-transform pair, then the characteristic function is

That is, the characteristic function is the Fourier transform of the random variable’s distribution function, with a change in the sign of the transform’s variable.

Connection to the Moment-Generating Function

The moments of the random variable can be easily obtained from the characteristic function by differentiation. Let’s take it slowly and take the first derivative of with respect to

,

Assuming (with good reason) that we can pass the derivative operation through the integral, we obtain

The derivative of the complex exponential is , so that the derivative of the characteristic function is simply

If we evaluate this derivative at , we obtain a scaled version of the first moment of the random variable

,

Now let’s look at the second derivative of the characteristic function–simply take the derivative of the first derivative (8),

or

which when evaluated at is a scaled version of the second moment of

,

By induction, we can apprehend the pattern, and prove the general result, for the case of the th derivative,

Since , we have the familiar form of the moment-generating function,

Another way of looking at this is to go back to (2), the definition of the characteristic function, and replace the complex exponential with its Taylor-series representation,

Replacing with

, we have the series representation

Substituting (17) into (2) yields

which agrees with the previous formulation.

If you can measure the moments of some random variable, then you can estimate the probability density function for that variable by computing the characteristic function through its series representation, and then Fourier transforming the result.

Connection to the Cumulant-Generating Function

Although it is difficult to prove in general (The Literature [R200]), the cumulants of are the coefficients of the series expansion of the natural logarithm of the characteristic function,

where is the

th-order cumulant of

.

Thinking back to our various examples of random variables, we recall that the probability density function for a Gaussian random variable with mean

and variance

is an exponential raised to a quadratic-in-

polynomial,

Because exponentiation and the logarithm are inverse operations,

the logarithm of the Gaussian PDF is a quadratic polynomial in . Therefore the series representation of that logarithm has only a first-order term and a second-order term, and so all cumulants with order three or greater are zero for a Gaussian variable.

Example

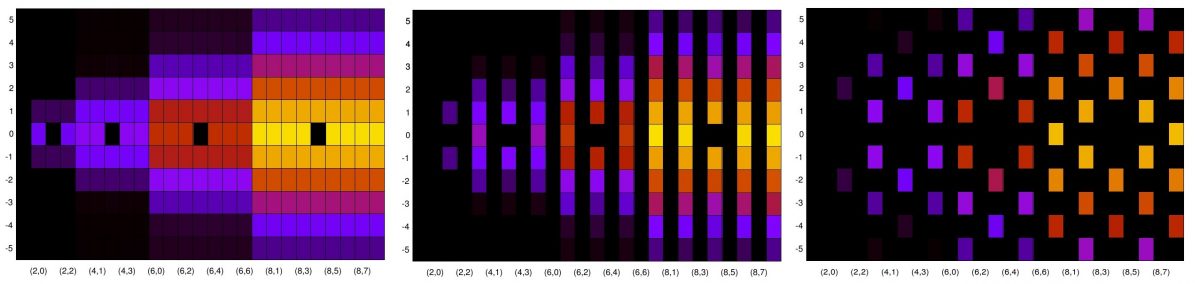

The characteristic function can be complicated, since it is the Fourier transform of a probability density function, or a joint probability density function, and such functions themselves can be arbitrarily complicated. Here, though, we wish to illustrate the concepts and the relationships between the various involved functions, so let’s showcase a simple random variable: the binary zero-mean random variable that takes on values

with some probabilities

.

The random variable is involved with our usual go-to example of the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal, and so is a pleasing and useful choice from the point of view of the CSP Blog. For the BPSK signal, we typically take

.

Viewing as a continuous–rather than discrete–random variable, the probability density function is impulsive,

The characteristic function is the Fourier transform of this density function, which is easy for us to evaluate,

Result (27) shouldn’t surprise us much if we recall the form of the Fourier transform of and

.

For our simple binary random variable , the characteristic function is a simple one:

. We can find the series expansion of

by following the general Taylor series formula, which involves finding all the derivatives of

, we can look it up, or perhaps some of us just remember it:

Note that we can express in terms of

by

Our series expansion for the characteristic function for is then

which when compared to (19) reveals that the moment is equal to one for even

and is zero otherwise. All the even moments of the symmetric binary random variable are equal to one. How can we check this? By directly computing the moments using expectation.

Let’s write the expression for the th-order moment for

,

which agrees with the series-expansion approach.

Turning to the cumulants of , we recall that these were provided in Table 1 of the post on PSK and digital QAM, up to an order of ten. The odd-order cumulants, like the moments, are zero, and the first five even-order cumulants are 1, -2, 16, -272, 7936.

Can we compute the logarithm of the characteristic function for as a series, thereby allowing us to confirm these cumulants? Let’s try. The logarithm of the characteristic function is

To find the series expansion, we can try to find the derivatives of this expression. The first derivative is

Recall from (20) that the th derivative of the logarithm of the characteristics function, evaluated at

is a scaled version of the

th cumulant

,

The first-order cumulant (mean) is equal to times the first derivative evaluated at

, which is

times

, or zero. Which checks out, since it is easy to directly compute the mean using the PDF–for the symmetric binary variable

with

, the mean is indeed zero.

The second derivative, evaluated at and scaled by

, is given by the derivative of the first derivative (38) or

Here we can substitute a known series expansion for to facilitate the differentiation,

where is a Bernoulli number. Now we need to take the first derivative of (41) to find the second derivative of the logarithm of the characteristic function, which will lead to the second moment when we scale and evaluate at

.

The lowest-degree power of in (41) corresponds to

, which is

, which will be the only term that is nonzero after setting

,

Now table lookup tells us that so that our second-order cumulant is given by

which checks!

Now we need the third derivative of the logarithm of the characteristic function, which is the second derivative of (41). Since appears in (41) only for odd orders

, the second derivative of (41) evaluated at

will be zero. This will be true for all even-order derivatives of (41), and therefore all odd-order derivatives of the logarithm of the characteristic function will be zero (which checks).

On to the fourth derivative of the logarithm of the characteristic function. The third derivative of (41) evaluated at will pick off the term associated with

, which corresponds to

. We have

which checks again.

The pattern should be clear now. is zero, and to get

, we’ll need the fifth derivative of (41) evaluated at

, which will pick off the term corresponding to

(

). This leads to

and with , we obtain

, as expected.

The eighth-order cumulant checks as well (-272), but I didn’t do the arithmetic for the tenth-order cumulant.

The Significance of the Characteristic Function in CSP

The characteristic function isn’t a function that I use much on the CSP Blog nor in my day-to-day signal-processing work. It isn’t quite as fundamental as the cumulative distribution function, the probability density function, expectation, moments, or cumulants. However, it plays a significant role in the theory connecting th-order moments to

th-order cumulants.

In CSP, most of our focus is on first- and second-order statistics and probabilistic parameters, such as the time-varying mean and the time-varying second moment (or variance when the mean is zero). And so we dwell on the cyclic autocorrelation and the spectral correlation function.

However, when we do employ higher-order statistics in CSP, it is almost always a cyclic cumulant, which is a Fourier-series component of the general periodically time-variant cumulant for a cyclostationary signal or process. Since the logarithm of the characteristic function has a series representation that explicitly involves cumulants, the characteristic function is a key part of the theory–if not the practice–of cyclostationary signals.

Complex Variables and Processes

You may have noticed that I focused on real-valued random variables in this SPTK post, whereas in our SP and CSP work, we almost always focus on complex-valued random variables, signals, and processes. There are some complications in extending the usual characteristic function to complex random variables. I take this up in My Papers [6] and you can also read about it on Wikipedia. The conclusion is that we can use the Shiryaev-Leonov moment-to-cumulant relation (The Literature [R200]) to form the cumulants of a complex random variable from its moments. Of course we need to be very careful about how we apply conjugations, but we’ve covered that in some detail here on the CSP Blog already.

Previous SPTK Post: I and Q Next SPTK Post: The Matched Filter

Hi Dr. Spooner – I *love* your blog! It’s like a living, growing CSP encyclopedia. Thank you for all the time and effort you put into it and for keeping it freely available to all. One quick typo (which admittedly doesn’t change the end result) is in equation (16) where the expansion on the RHS is still just in terms of rather than

rather than  . Looks like probably just a copy-paste-forgot to update kind of thing. Thanks again.

. Looks like probably just a copy-paste-forgot to update kind of thing. Thanks again.

Welcome to the CSP Blog Lauritz! And thanks for the comment.

I’ve fixed (16). Let me know if you find further problems.

If you want to use Latex to typeset some symbols or equations in a comment, use the dollar-sign delimiters, but just after the left dollar sign, add the keyword latex. I’ve edited your comment, and now the two symbols you included should appear as Latex-formatted math.

Finally, if you want to pitch in to help keep the Blog ad-free, please donate using the Donate button on the right side of any CSP Blog page. Strictly optional of course! But I do pay WordPress to keep ads off, and I pay for dataset and media storage on their servers.