We know that if we subject a cyclostationary signal to a squaring or delay-and-multiply operation we will obtain finite-strength additive sine-wave components at the output of the operation, where at least one of the sine waves has a non-zero frequency.

But I want to make a conjecture: All of CSP can be reduced to interpretations involving sine-wave generation by nonlinear operations. Let’s see if we can show this conjecture is true. After I make my attempt, I’ll also show what ChatGPT comes up with. Any guesses about how well it does?

Preliminaries

Suppose I’m given an infinitely long data record and let

be a power signal. How do I know if

contains a finite-strength additive sine-wave component with frequency

? That is, can

be written as

where cannot be expressed as

We know that a sine wave has a Fourier transform that is an impulse function, and that its power spectrum is also impulsive. So another way of formulating the question is: Can be written as the sum of a sine wave

plus a signal

with a non-impulsive power spectrum?

One way to check for the presence of the sine-wave component in is to perform an infinite correlation of

with the hypothesized sine wave

. That is, attempt the following calculation:

If the two limits exist separately, then the limit operation can be applied to them individually to find the sum. The second term has limit , which exists provided

is finite, which is a mild assumption.

What about the first term in (4)? Let’s call it ,

Now let’s introduce the familiar rectangle function, , which is defined by

to express as

Now recall the convolution operation from the SPTK post and elsewhere on the CSP Blog,

which means can be expressed as

Now let’s identify

Then

and

Now is the output of a bandpass filter with center frequency

and approximate passband width

. Since

has a continuous power spectrum, the power of

is finite, and we assert that the limit (14) is zero.

The conclusion is that a signal contains an additive sine-wave component with frequency , with non-zero amplitude, if and only if the infinite-time correlation between the signal and the sine wave

is non-zero.

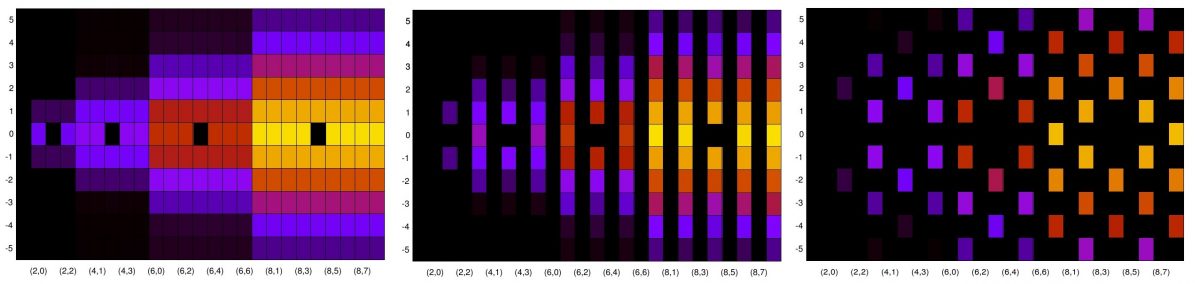

Figure 1 shows the result of a confirming measurement. Here I created a noisy unit-amplitude sine wave with frequency , a noise-only signal, and a noise-free unit-amplitude sine wave with frequency

. I then correlated the noise-only and noisy sine-wave signals with the noise-free sine wave for various correlation times and plotted the results.

Throughout the rest of this post, we consider a generic complex-valued power signal that is also a cyclostationary signal possessing at least one non-zero non-conjugate cycle frequency and one conjugate cycle frequency.

The various interpretations will be typeset in a quotation format, where the interpretation text will be left-bounded by a vertical line like this:

Interpretation.

Autocorrelation

In a stochastic-process framework, is a sample path of the stochastic process represented by

. For the process, the autocorrelation is defined as the mean value of the expected value of the product

,

In the fraction-of-time framework, the autocorrelation is simply directly calculated from using an infinite-time average

If the stochastic process is cycloergodic, which we assume is true, then the ensemble (SP) autocorrelation will equal the sample-path (FOT) autocorrelation almost certainly,

This means we can confidently focus on . By rewriting the formula for

, we can more clearly connect the autocorrelation with the concept of sine-wave generation,

which means that the autocorrelation can be interpreted as the strength of an additive sine-wave component in the lag product with frequency zero. That strength is a function of the lag variable

, and may be zero for some values of

.

is the complex strength of a zero-frequency sine wave in

.

Non-Conjugate Cyclic Autocorrelation

Continuing to assume the cycloergodic property holds, the non-conjugate autocorrelation for cycle frequency is given by

is the complex strength of a sine wave with frequency

in

.

Conjugate Cyclic Autocorrelation

Next we turn to the conjugate cyclic autocorrelation, which is equal to

is the complex strength of a sine wave with frequency

in

.

Spectral Density

In the fraction-of-time framework, the spectral density is a limiting case of the more general spectral correlation function–it is the non-conjugate spectral correlation with the cycle frequency equal to zero. In the stochastic-process framework, the spectral density is usually defined in terms of the expected value of the periodogram. If ergodicity holds, then the two spectral densities are equal.

The Wiener relation forges the connection between the autocorrelation and the spectral density: the spectral density, or power spectrum, is the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation function,

where denotes the Fourier transform operation. Here the Fourier transform is over the lag variable

.

How to interpret spectral density in terms of sine-wave generation? The dominant interpretation, for good reason, of the autocorrelation function is that it measures the self-similarity of a signal. It peaks at , where the signal

is identical to the signal

, and for most signals gets arbitrarily close to zero as

increases without bound, indicating that values of the signal very far from each other are unlikely to be similar.

But we’ve just developed an alternative interpretation of the autocorrelation in which the signal is a sequence of complex-valued zero-frequency (ZF) sine-wave amplitudes. Therefore the power spectrum is the representation of a set of regenerated ZF sine-wave amplitudes in terms of a weighted sum of all possible sine waves. That is, the power spectrum is the distribution of the generated ZF sine-wave amplitudes over frequency.

Is this trivial?

Let’s call the sequence of all possible (second-order, non-conjugate) sine-wave amplitudes for sine-wave frequency the amplitude signal

. Similarly, the sequence of all possible (second-order, conjugate) sine-wave amplitudes for sine-wave frequency

the amplitude signal

. Then

The power spectrum is then the Fourier transform of , which means the power spectrum is simply the spectral representation of the sequence of all possible second-order-generated ZF sine-wave amplitudes.

Consider the case where , where

is a complex number. The autocorrelation is

, a constant. No matter what lag

you choose, the generated ZF sine wave is the same. Consider that from the point of view of the self-similarity interpretation. Since the sequence of sine-wave amplitudes is constant, the spectral representation of the amplitude sequence should be an impulse at

, because it will take exactly one sine wave in the Fourier-transform representation to describe (represent) the sequence. And indeed, we already know that the power spectrum for a constant is an impulse at the origin.

Next consider the case where , where again

is a complex number. So here you can see that

specifies the sine-wave amplitude

as well as the sine-wave phase

, because

. What is the autocorrelation for a complex sine wave? We’ve been through this before, but let’s write it out again,

so that the autocorrelation function for a sine wave is that same sine wave with a different amplitude and zero phase. Which means that the amplitude signal for the sine wave is the sine wave too, so that the sequence of generated complex ZF sine-wave amplitudes oscillates forever with the frequency . The Fourier representation of that ZF amplitude signal is then restricted to a single sine-wave frequency,

, and an infinite amplitude. That is, the spectral density is an impulse at

with area

.

The power spectrum is the distribution of the generated zero-frequency sine-wave amplitudes over frequency. It shows how the generated ZF sine-wave amplitudes can be represented by an infinite number of infinitely small sine-wave components.

Non-Conjugate Spectral Correlation

Once we accept the sine-wave-generation interpretation of the power spectrum, the interpretation for the more general non-conjugate spectral correlation function–for cycle-frequency not equal to zero–follows easily as a slight generalization.

Recall that the amplitude signal for non-conjugate sine-wave generation is given by (26),

which is simply the complex amplitude of a sine wave with frequency generated by multiplying a signal by its delayed and conjugated self. Since the non-conjugate spectral correlation function is the Fourier transform of the cyclic autocorrelation, it is also the Fourier transform of the amplitude signal,

where the Fourier transform is over the lag (delay) variable .

This means that the spectral correlation function can be interpreted as the decomposition of the sequence of complex -frequency sine-wave amplitudes into an infinite number of infinitely small sine-wave components.

The non-conjugate spectral correlation function is the distribution of the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes

over frequency. It shows how the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes can be represented by an infinite number of infinitely small sine-wave components.

Conjugate Spectral Correlation

The interpretation of the conjugate spectral correlation function in terms of temporal sine-wave generation is similar to the interpretations for the power spectrum and the non-conjugate spectral correlation function.

The conjugate spectral correlation function is the distribution of the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes

over frequency. It shows how the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes can be represented by an infinite number of infinitely small sine-wave components.

Spectral Coherence

Before moving on to the higher-order functions of CSP, let’s attempt to interpret the spectral coherence function in terms of sine-wave generation.

Recall that the non-conjugate spectral coherence is a correlation coefficient, and can be expressed as the non-conjugate spectral correlation function normalized by the geometric mean of two spectral density values,

Sometimes I denote the coherence asand sometimes as

. Since we'll be using

below for cyclic cumulants, I'm going to stick with

here.

We’ve already interpreted the numerator of the spectral coherence (32) in terms of sine-wave generation, and we’ve interpreted each of the factors in the denominator as well. But now these various functions are combined in a highly nonlinear manner.

But notice that if the spectral density is a constant, say

, then the spectral coherence reduces to a simple scaling of the spectral correlation,

and so in this case, the interpretation of the coherence is identical to that for the correlation.

We’re interested in arbitrary (but cyclostationary) signals , though, so where does this lead us, if anywhere?

Consider the concept of a spectral whitening filter, or just a whitener. Suppose our signal has power spectrum

. Create a filter with transfer function

, and apply it to

to create

,

Then the power spectrum of is related to that for

by the relation

That is, like white Gaussian noise, the signal has a perfectly flat power spectrum, and therefore possesses equal amounts of all frequency components, similar to how white light contains equal amounts of all light wavelengths.

Therefore, for a whitened signal, the spectral correlation is equal to the spectral coherence, and so for the sine-wave-generation interpretation for the coherence is identical to that for the correlation.

The non-conjugate spectral coherence for

is the distribution of the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes

over frequency for its spectrally whitened version

. It shows how the generated

-frequency sine-wave amplitudes for the whitened signal can be represented by an infinite number of infinitely small sine-wave components.

A similar interpretation holds for the conjugate spectral coherence function.

Higher-Order Cyclic Temporal Moments

The th-order temporal moment function (TMF) for a complex-valued random power signal

is given by the expected value of the

th-order delay product with a particular conjugation configuration,

where is the fraction-of-time (FOT) expectation operation, which is also the periodic-component extractor, and

of the terms in the delay product are conjugated. For a cycloergodic random process

with sample path

, the more-familiar stochastic expectation can be used

For a cyclostationary signal , the TMF is a periodic (or almost periodic) function and so can be decomposed into a Fourier series as with any periodic function,

where the Fourier-series coefficients are the cyclic temporal moment functions and the Fourier-series frequencies

are renamed cycle frequencies.

From the preliminaries we engaged in earlier, it is clear that the CTMF represents the complex amplitude of a sine-wave component in the th-order delay product, where the frequency of that sine wave is the cycle frequency

. This is simply a generalization from second order to higher orders of the fact that the cyclic autocorrelation is the complex amplitude of a sine wave generated by quadratic processing (second-order delay product) of

. Therefore, the interpretation of the cyclic moment in terms of sine-wave generation is straightforward.

The

th-order cyclic moment

is the complex strength of a sine wave with frequency

in the

th-order delay product

.

Higher-Order Cyclic Temporal Cumulants

Recall that the th-order temporal cumulant function (TCF) is given by the usual moment-to-cumulant formula applied to the

th-order TMF and all the lower-order TMFs.

where is the set of all unique partitions of the index set

given by

.

The cyclic temporal cumulant function (CTCF) is the Fourier-series coefficient of a sine-wave component in the periodic (or almost periodic) TCF,

Clearly the CTCF (cyclic cumulant) is not the complex amplitude of a sine wave in some simple nonlinear function of . But if we remember the original development of the cyclic cumulant, we know that it is the complex amplitude of a pure

th-order sine wave, whereas the cyclic moment (CTMF) is the complex amplitude of an impure

th-order sine wave.

The

th-order cyclic cumulant is the complex amplitude of the sine wave with frequency

contained in the

th-order delay product

after all lower-order sine-wave products with frequencies summing to

are removed. It is the “what is unique here” sine-wave component in a higher-order delay product.

There are some difficulties with this interpretation, however, that we covered in the post on pure and impure sine waves. Notably, for rectangular-pulse PSK signals, there are pure sine waves (cyclic cumulants) with non-zero amplitudes even when the corresponding impure sine waves (cyclic moments) have amplitudes of zero. How can you purify something that doesn’t even exist?

Higher-Order Spectral Moments

The second-order spectral moment is just the spectral correlation function and is the most useful characterization of the cyclostationarity property. However, th-0rder spectral moment functions for

are the least useful. Nevertheless, we are attempting to confirm or disprove the conjecture at the top of the post: we can interpret all CSP parameters in terms of nonlinear sine-wave generation, so let’s proceed.

The finite-resolution th-order spectral moment is given by

where is our usual finite-time Fourier transform. The formal spectral moment function (SMF) is then the limit of this time average as the spectral resolution

approaches zero,

This function is not well-behaved for typical cyclostationary signals. In particular it can contain products of impulses. It can be shown that the spectral moment function is equal to the reduced-dimension spectral moment function (RD-SMF) , multiplied by an impulse that constrains the sum of the frequencies

to an

th-order cycle frequency

,

where the RD-SMF is the -dimensional Fourier transform of the reduced-dimension cyclic temporal moment function (RD-CTMF),

This is just the CTMF with one of the lags (delays) permanently set to zero. However, even the RD-SMF can contain impulses or products of impulses. But since we have an interpretation of the CTMF in terms of sine-wave generation, we have an interpretation of the RD-CTMF in terms of sine-wave generation, and so we have a path toward an interpretation of the RD-SMF in terms of sine-wave generation.

The RD-CTMF is the complex amplitude of a sine wave generated by an th-order nonlinearity (delay product with

factors using

conjugated factors). We can define a generalization to the amplitude signal given by

This means that the complex amplitude of the sine wave associated with the RD-CTMF is . As I demonstrated in the post on higher-order symmetry, and have discussed elsewhere, there are infinite sets of the delays over which

does not decay to zero. A special case of this property of the CTMF and RD-CTMF is the autocorrelation or cyclic autocorrelation for a sine wave, which are sine waves themselves. That is, the autocorrelation for a sine wave, as a function of the lag

never decays, which is why the PSD for a sine wave is an impulse, the PSD being the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation.

To see this more clearly for higher orders, consider a fourth-order delay product involving our old friend the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal,

We know that the first second-order delay product in (47) contains a sine wave with frequency zero as well as sine waves with frequencies equal to harmonics of the BPSK bit rate because the difference between the delays (

) is one, which is less in magnitude than the symbol duration of ten. Similarly, the second second-order delay product in (47) also contains sine waves with those frequencies, because the difference between delays is also less than ten.

No matter how big we make the delays in that second product, as long as their difference is small, we will have sine waves in the product. Therefore, the sine-wave amplitude will never be zero for any

.

The spectral moment function and reduced-dimension spectral moment function are the multidimensional frequency-domain representations of the complex amplitude of a sine wave that can be generated by a homogenous delay product such as

. They describe how the generated sine-wave’s amplitude behaves as a function of the delay vector. How many frequency components does it take to describe the generated sine-wave’s amplitude as a function of the multidimensional delay vector?

Higher-Order Cyclic Polyspectra

The higher-order spectral cumulants are the cumulants corresponding to the spectral moments in (41) (finite spectral resolution) and (42) (infinitesimal spectral resolution).

The finite-resolution spectral cumulant is given by

where is the approximate spectral resolution. The

operator is the moments-to-cumulant (Shiryaev-Leonov) operation that applies to any collection of

random variables. The

th-order spectral cumulant function is then the limit of this cumulant as the resolution approaches zero,

Similar to the case of the spectral moment, the spectral cumulant function is the sum of impulsive components,

where the weights of the impulses are the th-order cyclic polyspectrum, which is the

-dimensional Fourier transform of the reduced-dimension cyclic temporal cumulant function,

In these equations, is an

-dimensional vector of time delays, and the first

values of the frequency vector are denoted by the vector

,

Unlike the reduced-dimension spectral moment function, the cyclic polyspectrum is a well-behaved function for typical cyclostationary signals such as communication signals. This is because the reduced-dimension cyclic temporal cumulant function is the reduced-dimension cyclic temporal moment function with the various products of lower-order sine waves subtracted off–so it generally decays if any of the delays becomes large .

Since the interpretation of the RD-CTCF in terms of sine-wave generation has been developed here, and the cyclic polyspectrum is the Fourier transform of the RD-CTCF, we can interpret the cyclic polyspectrum in terms of sine-wave generation too.

The spectral cumulant function and reduced-dimension spectral cumulant function (the cyclic polyspectrum) are the multidimensional frequency-domain representations of the complex amplitude of a purified sine wave that can is contained in a homogenous delay product such as

. They describe how the purified generated sine-wave’s amplitude behaves as a function of the delay vector. How many frequency components does it take to describe the generated sine-wave’s amplitude as a function of the multidimensional delay vector?

Time-Varying Moment and Cumulant Functions

I did not supply explicit interpretations for the temporal moment and temporal cumulant functions (TMF and TCF), which are the time-varying moment and cumulant from which the cyclic temporal moments and cumulants are derived through the Fourier series. I’ll let you work that out, but a hint is that each of those time-varying functions is simply the sum of a possibly infinite number of distinct generated sine waves.

LLM Interpretation

Let’s check back in with ChatGPT. The last time I posted its knowledge (ahem) about CSP was in the interview post, and before that it was in the post of my first attempt at interacting with it. You’ll recall those did not go well for the LLM.

But the consensus seems to be that all the LLMs are improving at lightspeed or greater (the laws of physics are ignored in this context), so let’s take a look.

I wanted to know how ChatGPT would interpret the spectral correlation function in terms of sine-wave generation so I used the following prompt:

Provide an interpretation of the spectral correlation function in terms of sine-wave generation using quadratic processing.

I tried some harder ones too, such as interpreting the coherence, but the harder ones came out even worse. So here are the screen captures of the response:

How many egregious errors can you find? And this is after, I am certain, OpenAI has scraped the CSP Blog in its entirety. What it vomits out after that ingestion is terrible, and certainly will mislead many.

The “Glimpse” is particularly troubling as the right side is not a function of frequency , and is just the amplitude of a sine-wave component with frequency

in the function

. In other words, the non-conjugate cyclic autocorrelation for lag

and cycle-frequency

. On the other hand, ChatGPT readily asserts that the spectral correlation function and the cyclic autocorrelation function are in fact the same thing.

You might reflect on the confidently stated interpretation:

“When a signal is multiplied by its frequency-shifted version

the result contains sine-wave components at frequencies

.”

Where does frequency come from here? Also, when

is multiplied by

, the result is a time-varying function that potentially contains multiple (even many) additive sine-wave components, which we call the conjugate cycle frequencies for

. Then the factor

shifts all the conjugate cycle frequencies that are present in

. Muddled is a nice way of describing this interpretation.

Now try understanding the second sub-interpretation of the interpretation numbered “2.” Go on, I dare you.

So two-and-a-half years on, and it has not progressed on CSP. Probably never will since it has no means of checking its own work, no model of reality or truth, and in the meantime people will be using this kind of output to write papers and posts, which will then get ingested by ChatGPT. Thanks OpenAI!

Discussion

I hope this post helps build intuition about signal processing, and of course CSP, in the mind of the reader. Many of my posts are straightforward technical expositions, quite a few are rants or creative writing, and then there are the public post-publication paper reviews. This one is a bit different in that it doesn’t introduce significant new material, but instead attempts to explain and tie together various aspects of CSP that have already been presented in the CSP Blog, in My Papers, and in The Literature.

Did I succeed in tying all significant parameters of CSP to the concept of nonlinear sine-wave generation? Maybe. You be the judge.

If you have a reaction you’d like to share, or errors to point out, please leave a comment.