Let’s continue our progression of galleries showing plots of the statistics of communication signals. So far we have provided a gallery of spectral correlation surfaces and a gallery of cyclic autocorrelation surfaces. Here we introduce a gallery of cyclic-cumulant matrices.

When we look at the spectral correlation or cyclic autocorrelation surfaces for a variety of communication signal types, we learn that the cycle-frequency patterns exhibited by modulated signals are many and varied, and we get a feeling for how those variations look (see also the Desultory CSP posts). Nevertheless, there are large equivalence classes in terms of spectral correlation. That simply means that a large number of distinct modulation types map to the exact same second-order statistics, and therefore to the exact same spectral correlation and cyclic autocorrelation surfaces. The gallery of cyclic cumulants will reveal, in an easy-to-view way, that many of these equivalence classes are removed once we consider, jointly, both second- and higher-order statistics.

Review of Cyclic Temporal Cumulants

We develop cyclic cumulants from random-process theory in the cyclic temporal cumulants post. Let’s review the basic formula for an th-order cyclic cumulant before turning to the main topic of this post, which is the visualization of cyclic cumulants.

A cyclic cumulant is expressible in terms of cyclic moments, and both cyclic cumulants and cyclic moments are intimately related to the various th-order joint probability density functions of a cyclostationary random process or time-series. We can sidestep the density functions by just focusing on the moments and cumulants.

The most familiar (to signal processors) moment is the second-order moment

for some complex-valued signal . For a stationary signal, this moment is not a function of

, and it is usually renamed to the autocorrelation function. For a cyclostationary signal, this moment is periodic (or almost periodic) in

, and is expressible as a generalized Fourier series, the Fourier frequencies of which are the cycle frequencies, and the Fourier amplitudes are the cyclic autocorrelation functions.

To generalize the second-order moment to arbitrary orders , we consider a slightly more general version of (1),

then we also realize that the moment changes if we delete the conjugation on the second factor or introduce one to the first factor. So we consider conjugations by using an optional conjugation notation

as in

Now we can more easily generalize this second-order moment to orders by introducing an

-vector of delays

as in

Here the variable denotes the number of optional conjugations that are selected–it must range from zero to

. However, as I’ve noted elsewhere, this notation is not satisfactory because it does not specify exactly which factors in the product are conjugated. To remedy this, in the post on symmetries of higher-order cyclic functions, I introduce a binary vector

that has elements equal to one for the indices of

that are conjugated and elements equal to zero for those indices corresponding to unconjugated factors. So for

we get the non-conjugate cyclic autocorrelation with

, the conjugated non-conjugate cyclic autocorrelation with

, the conjugate cyclic autocorrelation with

, and the conjugated conjugate cyclic autocorrelation with

.

Now for cyclostationary communication signals , the moments (4) are periodic for some (usually all) choices of even

, and so we can express those moments in Fourier series

or if you like with the added specification of ,

The cyclic cumulant is a specific nonlinear function of cyclic moments. This follows directly from the well-known relationship between the th-order cumulant of a set of random variables and all the lower-order joint moments of subsets of those random variables (see the cyclic cumulant post for details). The cyclic cumulant is given by the following expression involving a sum of products of cyclic moments, where each product of cyclic moments has a set of cycle frequencies that sum to the cyclic-cumulant cycle frequency,

In this post, then, what we want to do is compute and display, somehow, the multidimensional function for a wide variety of communication signals for which these cumulants are not zero. And that is potentially helpful to us visually oriented humans because these cyclic cumulant functions are highly useful as features in signal-processing-based and machine-learning-based modulation-recognition algorithms and systems (My Papers [17,25,26,28,30,38,43,50,51,52,54,55]).

Visualizing Cyclic Cumulants

So how should we visualize these complicated multidimensional functions? One way I’ve tried in the past is to plot two-dimensional slices of the function and arrange them in a sequence indexed by the values of a third dimension, then show the sequence in a video. I do this in the cyclic-cumulants and higher-order symmetries posts. That works OK for fourth-order cumulants, but the dimensionality of sixth- and higher-order functions would lead to some very long videos indeed. In the fourth-order case, I can set , leading to the reduced-dimension cyclic temporal cumulant, fix

, the cycle frequency, and the conjugation configuration

, and then make plots of the cyclic-cumulant magnitude as a function of

and

. But for sixth-order cumulants, I’ve got too many delays to deal with for that approach to be viable.

Another possibility is to simply arrange all the cyclic cumulants in a giant matrix and plot that matrix using, say MATLAB’s imagesc.m. Let’s look at that for rectangular-pulse BPSK. Here the sampling rate is unity (as usual), the bit rate is 1/8, and the carrier offset is zero. I use 32,768 samples to estimate each cyclic cumulant (32,768/8 = 4,096 bits), delays ranging from -8 to 8, and cycle frequencies . Note that this set of cycle frequencies is sufficient to cover all BPSK cycle frequencies

because

.

I’ll consider cyclic-cumulant orders of 2 and 4 separately. The basic reason I don’t plot them all on one set of axes is that the dimensionalities of the two cyclic cumulant functions differ due to the delay vector. For , it is simply

and for

it is

.

All N=2 BPSK Cyclic Cumulants

Let’s first look at the cyclic cumulants for the ideal BPSK signal, and then we’ll take a quick look at the same functions for that BPSK signal after it experiences a simple multipath-channel impulse response.

All of the non-zero second-order () cyclic cumulant magnitudes and phases are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. To check my work, I plot a column of the matrix in Figure 1 in Figure 3. I chose the column corresponding to

and

, which is column 23. This column corresponds to the conventional autocorrelation, and we know that the autocorrelation for our rectangular-pulse BPSK signal is a triangle with width equal to twice the symbol interval, or 16. The height should be just greater than one, since the BPSK signal has unit power and there is a small amount of noise present. And from Figure 3 this all checks out.

All N=4 BPSK Cyclic Cumulants

Turning to fourth-order, the same three kinds of plots that we see in Figures 1-3 are shown for in Figures 4-6. Now you’ve literally ‘seen’ a higher-order cyclic cumulant! (I’ve posted the jpg images and the corresponding MATLAB .fig files on the Downloads page.) To check my work, I plot the 53rd column of the magnitude matrix in Figure 6 (see caption).

All Filtered-BPSK Cyclic Cumulants

The second- and fourth-order cyclic-cumulant functions for the ideal rectangular-pulse BPSK signal are estimated for a filtered version of the signal and shown in Figures 7-12. The filter is a four-ray multipath channel with delays 0.0, 2.0, 3.3, and 5.5 samples and associated complex-valued gains 1.0, -0.4+0.25i, 0.2-0.2i, and -0.1-0.07i.

So we can see that this method of visualization has a drawback–too much information is plotted. We can’t make much sense out of the fourth-order plots, so you can imagine that we’d have lots of trouble with the sixth- and eighth-order plots.

Fortunately there is another way.

The Gallery

The important, at least to me, aspect of the multidimensional cyclic-cumulant function is what I call the cycle-frequency pattern. We know that cycle frequencies depend on the order , the number of conjugated factors

, the signal’s probability structure (for example, the moments and cumulants of the symbol random variable), the pulse-shaping function, and even the particular values of the delay vector

(for example, consider rectangular-pulse signals and delays all equal to zero). For the broad class of digital PSK and QAM signals (and SQPSK and CPM/CPFSK), the cycle-frequency pattern can be discerned from a low-dimensional cut or slice of the full cyclic temporal cumulant function. In particular, we can set

and not render any cycle frequencies invisible (unlike for rectangular-pulse signals). So the cycle-frequency pattern is then some function

And for almost all of these types of signals, that function is

However, the cyclic-cumulant magnitude might be zero for some or even many of these cycle frequencies–the set of the cycle frequencies corresponding to all of the non-zero cyclic-cumulant magnitudes is the cycle-frequency pattern.

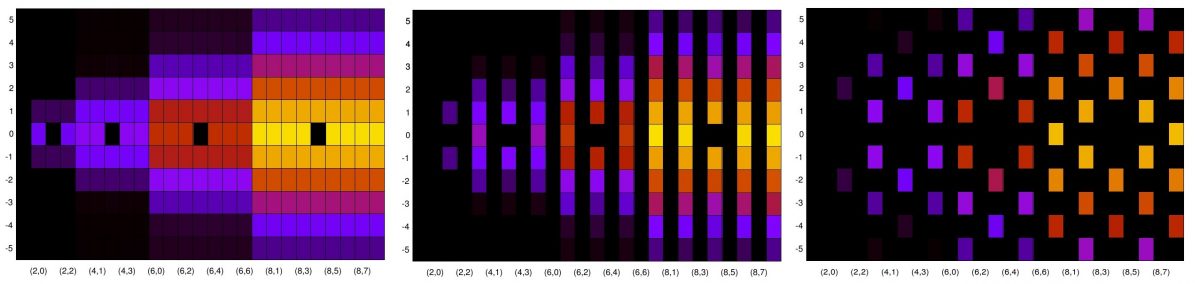

So an alternative visualization approach is to set the delay vector equal to the origin and find the cyclic-cumulant magnitudes and phases for all the cycle frequencies in (9), up to some maximum desired order, and plot those values. This gives rise to the style of cyclic-cumulant visualizations that form the banner of the CSP Blog–they are what I consider the fingerprint of a communication signal (I was using that term before the Machine Learners got their hands on it, sigh).

Of course there are complications even with this drastically dimension-reduced view of the cyclic cumulants. The main one is that typically the cyclic-cumulant magnitudes grow rapidly with , and so the dynamic range of the plot, so to speak, is high. The larger values (for larger

) will tend to dominate the plot. So the first thing we can do is raise each cyclic cumulant magnitude to the power

. This puts all the cyclic cumulant magnitudes on a equal footing with the power (

). The second thing we can do is plot the base-10 logarithm of that warped cyclic-cumulant magnitude. These steps render the cycle-frequency pattern easy to visually grasp–and that’s why we’re here after all.

Putting it all together results in the gallery of cyclic-cumulant features shown in Video 1.

The constellation definitions are shown in Figure 13.

Regarding the CPM and CPFSK feature plots, CPFSK is a CPM signal (The Literature [R188-R190]; My Papers [8]) with a rectangular pulse. All other CPM signals are called CPM, and the pulse type is indicated by a component of the name string. CPM signals can be partial-response signals or full-response signals, depending on whether the frequency pulse extends over more than one symbol interval (partial) or not (full). The underlying pulse-amplitude-modulated signal (that forms part of the argument of the carrier cosine) can have binary or larger alphabets. The alphabet size is also embedded in the filename. So, for example, the feature with title CPMLRC-0.3-3 is a CPM signal with raised-cosine pulses (‘LRC’), modulation index of 0.3, and the pulse spans three symbol intervals.

Hello Chad,

I am trying to blindly estimate HOCS plot (or as some call them Tetris plots). I managed to work out temporal averaging to blindly estimate temporal moment, then combine them according to (temporal) moment-to-cumulant formula and then take FFT of temporal cumulant to obtain cyclic cumulant. Now, I tried to use my machinery to your SRRC BPSK signal. I compute the temporal cumulant then shift it by -(n-2*m)*fc so it is zero-centered (also here one quick question, I think this should work to every modulation type, shouldn’t it?), have this stored in the memory, then take one sum-cumulant which consists of sum of absolute value of each of the computed cumulant. Then, I threshold this sum-cumulant to obtain peaks, more precisesly period of the peaks (I use the sum because I found out FSK signals I have available exhibit such pattern that is similar to SQPSK and if I tried to threshold each cumulant one by one, the found period would would actually be double the needed period). Since my cumulants are zero-centered, I take zero as the center and then take peaksFrequencies = +-k*peaksPeriod (where k goes from 0 to the value that is enough to cover [-0.5,0.5) interval). On these frequencies I take the absolute values of each of the cumulant and warp them, then save the value into a matrix that enteres the HOCS-plot.

My problem with this approach is that when I threshold the sum of cumulants (or even each of the cumulants) I tend to have too many frequencies, because I kinda “underthreshold” the peaks (https://imgur.com/a/pA6dRt0), or more precisesly there are small peaks that has a fixed period (in this SRRC BPSK it is double the carrier frequency) that are detected by the thresholding. Any suggestions or thoughts on this approach, how do you do your HOCS plots? I am aiming to use this in a modulation type estimate for which it would not be problematic as long as it underthresholds all the other signals I test against. The other approach could be that I assume the signal has type of modulation M as a null hypothesis and then reject if it doesn’t match. Any thoughts on this?

Have a good one 🙂

Jakub

Jakub: I’m not fully understanding your approach. Can you restate the first paragraph using math?

The way I provide most of the plots in the Cumulant Gallery post is by evaulating theoretical formulas for the cyclic cumulants. The formulas are known for all MPSK, MQAM, and CPM (including MSK and SQPSK, but also many others) signals. For those signals where I don’t have an explicit formula, I just ask ChatGPT.

Kidding!

For those cases, I estimate from high-SNR simulated or captured data.

But the crucial thing is that I do signal processing operations on the data to get at three things before I try to estimate the cyclic-cumulant matrix:

1. The cycle-frequency pattern

2. The symbol rate

3. The carrier frequency offset

Once I have those, I can estimate the cyclic moments directly (no thresholding needed, since I know the cycle frequencies from (1)-(3)), then use the cyclic-moments-to-cyclic-cumulants (Leonov-Shiryaev) formula.

Thanks for the response, I’ll try to formulate what I am doing more carefully. (Note that I ommited the iterators itn and itm in the code snippets that should be there for the code to be working)

TpOptimal = 1;

for n = [1, 2:2:8]

for m = 0 : n

[tcf{itn,itm}, TpAllFound] = computeTemporalCumulant(tau,n,m);

TpOptimal = lcmArray([TpOptimal, TpAllFound])

end

end

where computeTemporalCumulant utilize this formula:

where the moments are obtained using Synchronized Averaging (i.e. blindly estiamted). The Synchronized Averaging returns blind estimate of the temporal moment function (for the given partition) and Tp (the period at which is tha largest power-drop in the residual power).

Then after having all the needed temporal cumulants I compute cyclic cumulants:

% N-mod for better FFT quality, *2 to make Nfft even so that frequencies contain zero

Nfft = N – mod(N,TpOptimal*2);

Nscale = min(Nfft,N) ;

ctcfFreqs = (-Nfft/2:(Nfft-1)/2)/Nfft;

for n = [1, 2:2:8]

for m = 0 : n

% compute cyclic cumulant

ctcf{itn,itm} = 1/Nscale*fftshift(fft(tcf{itn,itm},Nfft));

% shift -(n-2*m)*fc

fcSamples = fc*Nfft;

if n == 1

shiftToZero = 0;

else

shiftToZero = -(n-2*m)*fcSamples;

end

ctcfZeroCentered{itn,itm} = circshift(ctcf{itn,itm},shiftToZero);

% sum cumulant

ctcfsum = ctcfsum + (abs(ctcfZeroCentered{itn,itm}));

end

end

Then I threshold the ctcfsum, because it contains all the frequencies (as I mentioned in the previous comment)

% find period of peaks in sum of all abs(CTCF) (period is in samples)

peaksPeriodSamples = findPeaksPeriod(ctcfsum,ctcfFreqs);

% center around zero

[~,k0] = min(abs(ctcfFreqs));

% find indices of peaks

k1 = floor((Nfft-k0)/peaksPeriodSamples);

k2 = floor((k0-1)/peaksPeriodSamples);

k = min([k1,k2]);

indicesAll = k0+(-k:k)*peaksPeriodSamples;

And lastly I simply iterate through (n,m) again and obtain the HOCS matrix:

% save values to matrix

cumulant = abs(ctcfZeroCentered{itn,itm});

hocsMatrix(:,it) = (cumulant(indicesAll).^(2/n));

xtickLabels{it} = sprintf(‘(%d,%d)’,n,m);

So for this to be working I only need to know the carrier frequency, which can be obtained from conjugate SCF, or cyclic moment/cumulant. To follow up: symbol rate can be obtained from the SCoF (spectral coherence function), is it true for every modulation type? Also, big struggle I always have is that I don’t know how to obtain the cycle-frequency pattern. I know there’s theory, however, even the premodulation filtration changes CF patterns. Moreover, is there a way to find CFs blindly (or partially blindly with the use of fc and symbol rate)? Do you have any summarizing post that describes what tool is good for what parameter estimate and wheter it applies for every modulation type (and it does not apply then for what types)? I think this would be great post for CSP beginners as, to me at least, it was (and sometimes still is) not always clear.

This seems like it will produce at best a rough approximation to the cyclic-cumulant matrices shown in the post.

I don’t think the summation of the Fourier transforms of the temporal cumulant functions (TCFs) is a good idea in general. Many of the TCFs that you compute with the synchronized averaging will correspond to for which the underlying signal has no cyclostationarity–so you’re just adding noise to the running sum.

for which the underlying signal has no cyclostationarity–so you’re just adding noise to the running sum.

Also, the synchronized-averaging approach to TCF estimation is not easy–if the period(s) of cyclostationarity are not equal to integer multiples of the sampling increment (reciprocal of the sampling rate), there will be a bias in the estimate.

Before I say more, what exactly is findPeaksPeriod()?

The function findPeaksPeriod() thresholds the sum of cyclic cumulants, starting with small threshold 1e-12. It finds the positions (indices) which pass the threshold, then diff is computed and unique diff values are taken (let’s call it diff_vector). GCD of the diff_vector is then computed. Note that all this happens in indices, not in frequency units, so for example when the length of the cyclic cumulant is Nfft and the diff between two peaks is 100 indices, it corresponds to period of the peaks 100/Nfft in frequency units. If GCD equals one then increase the threshold and repeat, elseif GCD(diff_vector) == min(diff_vector) then return this value. It happened that in my SRRC BPSK testing this approach found smaller period than what are the native cycle frequencies (see the imgur link I sent earlier), specifically it found peaks-period corresponding to carrier frequency.

Regarding the computation of the CTCF, are you using the formula (7) in this post and in your codes in general? I tried to use it but the computation was kinda cumbersome in a way I couldn’t generalize it easily, whereas the approach that uses sum of temporal moments is relatively easy to implement. I managed to compute the cyclic cumulant for BPSK signal using the formula (7) with the known cycle frequency pattern. However, it was obviously wrong, yet I didn’t delve into it so I dont’t know what was the problem. Should the formula (7) be used, the question arises again, how do you estimate CFs? In your paper [26] in the classification algorithm you mention “Estimate and group higher-order CFs” but I don’t see how the estimate should be perfomerd, also what does “group CFs” mean?

And about the bias in the synchronized averaging, yes that’s true. However, this bias should be lowered (or removed) by truncating the signal so that its length is multiple of the symbol period, or am I oversimplifying?