Dr. Snoap’s final journal paper related to his recently completed doctoral work has been published in IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting (My Papers [56]).

I previewed this paper when I described an earlier and incomplete version of it, which is My Papers [55]. The idea is to construct novel neural-network preprocessing layers that convert a sequence-classification problem into an image-classification problem. Why do that? I do explain my answer to that question in the [55] post, and some of that explanation also made it into the published [56] paper. The gist is that convolutional neural networks are great for image recognition–they are directly inspired by early [20th century] models of the human eye-brain image-recognition system–but not so great for sequence classification when the sequence has no obvious connection to a human-recognizable image. That is, a plot of the I/Q samples for some slightly noisy PSK or QAM signal isn’t readily distinguishable from a plot of I/Q samples of noise or from a plot of I/Q samples of some other PSK or QAM signal.

But we can convert such sequences into objects that when plotted do look like recognizable objects in the world, or at least have features that edge detectors, matched filters, HPFs, LPFs, etc., would easily pass or reject.

Why doesn’t the convolutional neural network, which has plenty of nonlinearity to it [not the convolutions, but other layers], just “learn” to create the kinds of transforms I’m talking about? That’s a tough question, though, and all my machine-learning co-workers have a hard time interrogating their machines to try to answer it. What exactly is being learned? Why aren’t valuable things being learned?

In the end, the novel-layers approach nudges the network toward extracting powerful features, where I’m using powerful here to denote features that lead to both high classification performance and high degrees of generalization. That latter aspect of the network just means that the classification performance is not sensitive to smallish changes in the probability density functions of key underlying modulation-related random variables.

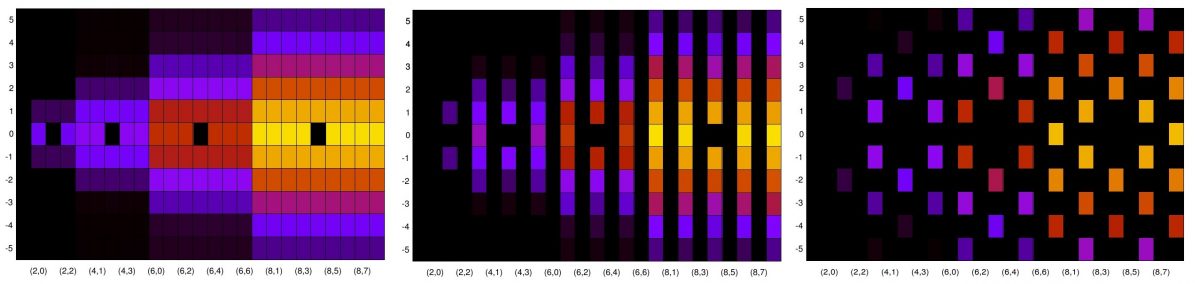

Figure 1 below shows Figure 1 from [56], which is the high-level description of the network architecture that John developed. The layers at the front of the network are homogeneous nonlinearities, like squarers, and also the Fourier transforms of such nonlinearities. The nonlinearities produce sine-wave components, which is nothing more than exploiting cyclostationarity [as you know, dear reader!], and the transforms produce vectors with a small number of large components–spikes that are easily detected by, say, bandpass filters [convolutions].

The work is motivated by the observation we made (which is not unique to us) that trained neural networks of image-processing provenance can produce very high probabilities of correct classification on one dataset or another, but tend to fail when trained on one dataset and applied to another, even when the datasets contain the same modulation types and rough ranges of parameters. If there are even small differences in the probability density functions for those parameters between the datasets, whatever the network learns by being trained on one is not terribly relevant to use on the other.

One way out of this, which represents a couple of the papers produced by John during his doctoral work, is to simply train a network using features we know generalize well. These features must have some invariances with respect to the parameters that are likely to be different over various datasets. For example, we’d want to be able to recognize a BPSK signal no matter what the numerical value of its rate is–the feature that corresponds to BPSKness should not depend on such values. Fortunately, such features can be constructed from the cyclic autocorrelation, spectral correlation function, and most importantly, the cyclic cumulants. When we train image-processing-style networks using cyclic-cumulant features instead of I/Q samples, we do indeed obtain high performance and high generalization (My Papers [52,54]).

But that kind of signal-processing feature-extraction work, coming as it does before the network, is exactly what the current crop of engineers is trying to avoid. They don’t want to deal with domain knowledge. Why can’t the machine figure it out? Why, indeed. So to avoid domain knowledge, and to avoid constructing correct cyclic-cumulant feature extraction software, we attempt novel layers. We are trying to get the benefits of domain knowledge (invariant features) combined with the avoidance of domain knowledge. Which seems paradoxical. I guess it is, because, well, why do we select the particular layers we do? Domain knowledge.

If you think your approach to a trained (supervised-learning) neural network has a high degree of generalization, then the CSP Blog’s Challenge for the Machine Learners and the associated Generalized Challenge are for you. So far, no one has submitted modulation-type labels for the Generalized Challenge, after training on the Challenge, that are anywhere near correct. I assume that if I was wrong, and all of this is easy, I would have been flooded with high-generalization responses, but that hasn’t happened and the Challenge stands. (See the Comments here for the responses I’ve received).

Hello Professor,

You have provided answers to questions that have been on my mind these past few days while reading these two articles.

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8879545

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38248155/

Could you enlighten us more on the weaknesses of these two papers?

By the way, I’m rather probabilistic guy and I’m more confortable with Pr Giannakis papers than your deterministic approach. Any advices ?

Great Fat Thank You Professor for such great ressources.

Sadok_Mu: I haven’t read those papers, but I have them now. I will reply after I digest them. At that time, I’ll attempt a response about the ensemble-vs-FOT question, but you could probably predict my answer.

First, those two papers are on “RF Fingerprinting,” which is the modern name for “specific-emitter identification” as applied to communication signals. I did a little bit of work on that in the past (My Papers [10,33]).

The paper that is the subject of the post, My Papers [56], is on modulation recognition. The difference is that in mod-rec, the statistical differences (or more theoretically the probability structures) of the various signals are fairly different, and in the RF fingerprinting case, they are tiny. In the mod-rec case, the differences arise from the modulation process itself, which takes bits to a transmitted electromagnetic wave. In the RF fingerprinting case, the differences arise from the transmitter hardware itself, which has small imperfections or deviations from design-specified parameters.

In some cases, things like I/Q imbalances can in fact be accurately detected/characterized by CSP. In my main mod-rec system, I have computed cyclic-cumulant features that correspond to specific pairs of (mod-type, iq-imbalance). Unless the imbalance is small, this can work. However, unlike some of the statements in modern RF fingerprinting cases, these imbalances really are pretty small. In other cases, an imperfection in the hardware of the transmitter will be averaged away in the computation of cyclic cumulants or the spectral correlation function.

So overall those two papers aren’t really relevant to [56].

They have some standard weaknesses, including small dataset sizes, and narrow focus. As will all supervised-learning DNN papers/studies, if you work hard enough on the layers of the network, you’ll eventually train the network into a small error and high probability of correct classification. In the RFAL paper, there are some claims about the efficacy of ML/DNNs that I’ve debunked many times, but that’s understandable due to the publication date of the paper. For example,

“An in-depth study on the performance of deep learning based radio signal classification was presented in [33] (O’Shea). The authors considered 24 modulation schemes with a rigorous baseline method that uses higher order moments and strong boosted gradient tree classification. The authors also applied their method to real over-the-air data collected by SDRs.”

We know that O’Shea and company did no such rigorous study and that there is zero evidence that they even understand what a moment is.

“All the traditional techniques that have been used for RF analysis lack flexibility and robustness.” Just not true. CSP-based techniques are *more* robust to differences in the PDFs of involved random variables than CNNs/DNNs (with I/Q at the input).

The correlation plots, and the motivation for them, in Figure 2 are deeply mysterious to me.

* * *

I don’t think there is a big problem with being a “probabilistic” guy. You’ll notice that throughout the CSP Blog, I use expectations. I also spent a bunch of time on the SPTK series building up probability theory because it is so important to us in signal processing. So go ahead!

The importance of the fraction-of-time (FOT) probability theory isn’t so much as a useful day-to-day tool, but to help us really understand the pitfalls of using complicated random processes to model communication signals and scenes. That is, ergodicity and cycloergodicity. Just be careful when you add random variables to your model–you may end up destroying cyclostationarity “on paper” and yet it still exists and is exploitable for almost every encountered time series (sample path).

I’m currently experiencing some difficulties implementing the network. Would you mind letting me know if you have any plans to open source it? Thank you.

student: Welcome to the CSP Blog!

No, I don’t have any plans to open source the networks that Dr. Snoap and I created.

What “difficulties” are you having?

I view the novel-layers networks as suggestions regarding a possibly valuable course-correction in RFML rather than a definitive final answer to the problem. I realize you might want to implement the network in order to compare to something else in a paper, but I think we gave sufficient information to permit a knowledgeable practitioner to do that. Let me know if we did not!

For me, the key question is why the new approach requires a BOI filter while the cumulant-net does not. It seems analogous to a match filter with measurement errors—so do these errors significantly affect overall performance?

I take it the “new approach” is what we have been calling the “novel layers” or “novel network layers” approach.

I take it “cumulant-net” means a mod-rec neural network that accepts cyclic-cumulant matrices, rather than I/Q data or spectrograms or whatever else, as the input.

The cumulant-net approach we’ve written about does have a “boi filter,” which I take to mean a signal-processing algorithm that automatically detects the occupied bandwidth of a signal, isolates it by linear time-invariant filtering, shifts it to approximately zero frequency, and optionally resamples to ensure the fractional bandwidth is appropriate for second- and higher-order statistical signal processing. (Automatic spectral segmentation.)

Once the cumulant-net approach finishes blindly extracting the cyclic-cumulant matrix, the center frequency of the signal has been (very) accurately estimated so that all the signal’s cycle frequencies can be known and therefore the cyclic cumulants can be accurately estimated. You just don’t see all the steps required to get to the cyclic-cumulant matrix in a high-level block diagram of something like the cumulant-net.

Novel Layers: Uses a spectral-segmentation step in preprocessing (boi-filter)

Cumulant-Net: Uses a spectral-segmentation step in preprocessing (boi-filter)

Snoap/Spooner I/Q Nets: Do not use a spectral-segmentation step in preprocessing (there is no preprocessing)

Others’ Spectrogram Nets: Do not use a spectral-segmentation step

I think a good research goal is to further develop the Novel Layers concept so that a spectral-segmentation preprocessing step is either not needed or its accuracy can be poor (the signal is only very approximately “basebanded”).

Does that help?

Dear Dr. Chad,

Thanks for sharing Dr. Snoap’s work with us. It’s really fascinating to see an ingenious combination of conventional CSP and DL delivering a solid performance! I was reading your earlier work titled “Deep-Learning-Based Classification of Digitally Modulated Signals Using Capsule Networks and Cyclic Cumulants”. I am wondering how crucial is the 3rd step of procedure for extracting signal parameters: “Downsample/upsample the data as necessary such that the signal bandwidth is maximized, but keep the fractional bandwidth of the result strictly less than 1.”

Following the discussion on your blog, Resolution in Time, Frequency… for CSP Estimators, it is advisable to use the largest possible block-length, to get high TF product. Therefore, it seems plausible to not downsample a signal, unless there is a risk of aliasing due to subsequent nonlinear operations, i.e., SSCA/Step 8. In normalized frequency, a signal with highest frequency component less than 0.25 (approximately speaking) would not need to be downsampled, provided it has a computationally managable block length.

On the other hand, the requirement for upsampling is not immediately clear. Is it only to avoid aliasing, resulting from subsequent nonlinear operations, or it can improve the resolution at the output of SSCA (due to increased block-length)? Can you please elaborate?

Also, what does it mean to maximize the bandwidth of the signal?

Can you please help in understanding better?

Welcome to the CSP Blog mohitsharma! I appreciate the comment very much. Let me try to help with a response.

For other readers, the paper referenced here is My Papers [54]. Here are the steps in question:

So these are steps aimed at “getting ready” to estimate the cyclic cumulants by blindly determining what I call the cycle-frequency pattern.

The reason I want to resample so that the fractional bandwidth (ratio of the signal’s occupied bandwidth to the sampling rate) is close to one is to minimize oversampling, which in turn means that for a data-record length of seconds, we are representing that data with a minimal number of samples. That, in turn, means that the SP and CSP algorithms operating on that data record will have minimum complexity.

seconds, we are representing that data with a minimal number of samples. That, in turn, means that the SP and CSP algorithms operating on that data record will have minimum complexity.

Keep in mind that when I say to use as large a block length as possible in CSP, I don’t mean to suggest you achieve a long block length by resampling. I mean use as many seconds as possible.

And yes, once we start estimating the cyclic cumulants, we’ll be using fourth- and sixth-order nonlinear operations, and if we are not properly oversampled at that point, cycle frequencies will alias and cyclic-cumulant estimates become distorted.

So the desired fractional bandwidth for the second-order steps (cycle-frequency pattern estimation) and the higher-order steps (cyclic-cumulant estimation) will differ. You need a lower fractional bandwidth (more oversampling) for the latter than for the former.

See above. It is only for properly estimating cyclic-cumulants. Oversampling a data record cannot improve resolution. Imagine taking 10 samples of a BPSK signal with bit rate 1/10 (one bit). If oversampling could help estimator resolution here, we could just oversample that one bit to the moon, and somehow get good results. But that doesn’t work–it is the number of instances of the underlying random variable that determine the stability and resolution capabilities of an estimator.

I mean fractional bandwidth here. So, adjust the sampling rate of some sampled-data vector so that the fractional bandwidth of the signal is close to unity. I don’t mean to imply that you have to do something to the transmitter, such as increasing the symbol rate or changing the square-root raised-cosine filter.

Does all that help?

Thank you very much, Dr. Chad. I truly appreciate your patience and the detailed explanation and clarification! It is very helpful.

I also found the same through simulations. Downsampling the signal with a factor of 2, does not affect both the conjugate and non-conjugate cycle frequencies (CFs). In particular, for a signal downsampled by a factor of 2, the CFs observed were 2 times of the CFs observed for the original signal. I inferred that, to correctly interpret/plot the SSCA output for downsampled signal, one need to also map the normalized frequency range using a corresponding downsampling factor. Can you please confirm, if the above understanding is correct?

In addition, would it be possible for you to answer the following questions related to my implementation of the your above mentioned paper?

1) I observe some spurious cycle frequencies in my SSCA output, for Signal_1 and Signal_4000, particularly in Non-conjugate CFs. I am wondering, generally, what causes these spurious frequencies, a not so apt choice of hyperparameters?

I have uploaded my code and results at the following: https://github.com/AmrahsM/CST_test.

2) Amplitude of spikes, based on both SCF and Coherence function does not match the output shown in the dataset webpage of this blog. I believe, this is because of normalization used for window functions a(.) and g(.). Is it correct?

3) I am wondering, how robust is the subsequent cyclic cumulant computation, is with respect to estimation errors incurred in cycle frequencies. I feel that, a reasonably accurate estimate of cycle frequencies should result in a similarly looking CC-estimates pattern.

Thank you again for your patience and time.

Any pointers on how to debug the code to fix the spurious cycle frequencies would be really helpful..

Yes, if you resample a signal, and that resampling does not distort the signal, then the cycle frequencies of the resampled signal will reflect that resampling. , then if you resample and still use a sampling rate of 1 for the new data, you’ll get a set of cycle frequencies

, then if you resample and still use a sampling rate of 1 for the new data, you’ll get a set of cycle frequencies  that differs from

that differs from  . However, if the original data is associated with a physical sampling rate

. However, if the original data is associated with a physical sampling rate  , and the resampled data is associated with

, and the resampled data is associated with  , and you make sure to properly account for the sampling rate, then the observed cycle frequencies for the original data and resampled data will be the same.

, and you make sure to properly account for the sampling rate, then the observed cycle frequencies for the original data and resampled data will be the same.

If you are using a sampling rate of 1, and you observe cycle frequencies

Before we can get to “spurious cycle frequencies,” we need to make sure that the prominent observed cycle frequencies in your plot match the known parameters of the input signal. Looking at your plots, I see there is a fundamental problem with either computation or interpretation. For the non-conjugate cycle frequencies, you should always see a prominent peak at , which reflects the power of the input data. But in your non-conjugate plots, there is no peak at

, which reflects the power of the input data. But in your non-conjugate plots, there is no peak at  . There is a nearby peak, but it is not at

. There is a nearby peak, but it is not at  .

.

I tried to run your python code, but it has errors. Line 91 is missing a “def” and you did not supply the read_binary module.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File “./CST_blocks_CSPB.py”, line 5, in

from read_binary import read_binary

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named ‘read_binary’

I assume that signal_1.tim and signal_4000.tim are from the remade 2022 dataset (CSPB.ML.2022R1). Looking at the BPSK signal signal_1.tim, then, you should see a prominent non-conjugate cycle frequency of 4.3858048e-02.

Have you gone through the estimator-verification process described here? I think that is a crucial step in development of CSP code.

Thanks a lot for taking time out to explain the concept, and running my code. The impact of resampling on cycle frequencies is clear now.

I also appreciate you flagging the fundamental issues in the implementation. Your feedback is helping me realize where I need to revisit my understanding and approach. And thank you for pointing me toward the estimator verification process which I initially missed — I’ll go through it, and will carefully analyze my code.

However, I bench-marked my SSCA implementation for BPSK signal, and my plots for SCF and coherence looked visually similar to your results, posted on SSCA blog. I have also uploaded the source file used for BPSK signal analysis, named test_estimator, and its associated results, in the above Github repo. The plot files are named as ‘….._BPSK.png’.

Further, the Signal_1 and Signal_4000 belongs to the CSPB.ML.2018.R1. These are the same signals for which you have provided the plots on the Machine-learning challenge dataset webpage, i.e., the following.

https://cyclostationary.blog/2019/02/15/data-set-for-the-machine-learning-challenge/

In the CSPB_CST_blocks.py, I am trying to match the estimates provided by you. I assume, while plotting the non-conjugate cycle frequencies you exclude the spike at , is that correct?

, is that correct?

I’ll take some time to clean things up and get back to you with the corrected version. Really grateful for your time and guidance!

I see on those aerial plots that the SSCA-detected cycle frequencies have the same flaw as in your CSPB.ML.2018 cyclic-domain-profile plots–they are shifted relative to truth. For the rectangular-pulse BPSK signal with bit rate 1/10, the non-conjugate cycle frequencies are . You can see that they are not falling close to the grid lines, and the gap increases with

. You can see that they are not falling close to the grid lines, and the gap increases with  .

.

Thanks for the update on just which “signal_1.tim” and “signal_4000.tim” files we are talking about!

For signal_1.tim, then, the rate is . On your plot Signal_1_NCF_DSF_1_SCF.png, the reported bit-rate cycle frequency is

. On your plot Signal_1_NCF_DSF_1_SCF.png, the reported bit-rate cycle frequency is  and the central peak (presumably the true

and the central peak (presumably the true  peak) is at

peak) is at  , which is suspiciously close to

, which is suspiciously close to  . So your cycle frequencies are shifted by some simple function of the reciprocal of the number of strips

. So your cycle frequencies are shifted by some simple function of the reciprocal of the number of strips  , which is itself presumably a dyadic number

, which is itself presumably a dyadic number  .

.

Yes, when I use the cyclic-domain-profile plot style, I typically leave off all non-positive cycle frequencies due to symmetry and lack of interest in seeing the height of the peak.

peak.

Thanks a lot Dr. Chad for pointing towards that shift in cycle frequencies, it is really helpful and reassuring to get your feedback on my plots. I’ll debug my code to fix the source of this shift.

I have a couple of more questions, related to your work [54] which is mentioned above:

1) What is the difference between Step-4 and Step-7? Both seems to achieve the same task, i.e., to determine the second-order CFs. Can you please elaborate on this?

2) This one is related to Step-8, and the need to determine the CF pattern to compute the CCs for n=4 and 6. Is it required to explicitly use ‘Further CSP’ to determine the pattern of CFs for n=4 and 6, or the one obtained using eq. (7) can be used to compute CCs? If needed, what are these ‘Further CSP’ tools for determining the CFs for n=4 and 6, can you please refer me to some sources where I can learn about it?

Thank you again.

Step 4 is the application of the SSCA to the data (apply twice to obtain the non-conjugate cycle frequencies and the conjugate ones).

Step 7 processes the outputs of Step 4 to determine the basic CF pattern exhibited by the signal: BPSK-like, QPSK-like, SQPSK-like. If the pattern is QPSK-like (no conjugate CFs, just one non-conjugate CF), then there is no detected cycle frequency related to the CFO, so you have to resort to fourth-order processing to determine the quadrupled carrier (see the synchronization post).

Once you look at the FFT of , you can infer which CF pattern the QPSK-like signal exhibits: QPSK-like, 8PSK-like, or

, you can infer which CF pattern the QPSK-like signal exhibits: QPSK-like, 8PSK-like, or  -DQPSK-like. You will have to study these things to see what I’m talking about. I think there are some graphs of these things somewhere on the CSP Blog. I’ll try to find, but go ahead and look too.

-DQPSK-like. You will have to study these things to see what I’m talking about. I think there are some graphs of these things somewhere on the CSP Blog. I’ll try to find, but go ahead and look too.

Thank you Dr. Chad for the explanation, I’ll read about it.

Hi Dr. Chad, Thanks again for pointing that the frequency shift for non-conjugate cycle frequencies equals . That has helped me to fix the issue related to shift in the non-conjugate cycle frequencies by accounting for the residual at the both end of

. That has helped me to fix the issue related to shift in the non-conjugate cycle frequencies by accounting for the residual at the both end of  and

and  , instead of directly mapping

, instead of directly mapping  and

and  to -0.5 to 0.5 and -1 to 1, respectively. Now, I am trying to fix a similar shift issue for conjugate cycle frequencies. For the 32768 samples and

to -0.5 to 0.5 and -1 to 1, respectively. Now, I am trying to fix a similar shift issue for conjugate cycle frequencies. For the 32768 samples and  , the conjugate cycle frequencies are shifted by

, the conjugate cycle frequencies are shifted by  . I am wondering how the mapping between

. I am wondering how the mapping between  to

to  changes. I tried plotting conjugate CFs by replacing the variable

changes. I tried plotting conjugate CFs by replacing the variable  by

by  in the mapping equations, but it does not work. Am I understanding correctly?

in the mapping equations, but it does not work. Am I understanding correctly?

I don’t think the mapping changes.

When you do a conjugate coherence, you have to change the way you select the two PSD values that form the denominator though.

Thanks for clarifying this. Interestingly, my conjugate SCF based spike plots also show the same shift.