My Old Dominion colleagues and I have published an extended version of the 2022 MILCOM paper My Papers [52] in the journal MDPI Sensors. The first author is John Snoap, who is one of those rare people that is an expert in signal processing and in machine learning. Bright future there! Dimitrie Popescu, James Latshaw, and I provided analysis, programming, writing, and research-direction support.

The new paper is titled “Deep-Learning-Based Classification of Digitally Modulated Signals Using Capsule Networks and Cyclic Cumulants,” and is My Papers [54]. If you go to the My Papers page, you can download a pdf of the new paper using a link in the citation for [54].

In the extended paper [54], we provide additional details of cyclic-cumulant estimation and direct comparisons to a CSP-based blind modulation-recognition algorithm (My Papers [25,26,28]). The discussions concerning motivations, processing approaches, and future directions are also extended relative to [52].

Like [52], the focus of [54] is on the generalization problem associated with trained neural networks. In our application area, modulation recognition, and in many other areas, a major drawback of using trained neural networks (convolutional neural networks, residual networks, capsule networks, etc.) is that their performance is highly sensitive to slight changes in the probability density functions that describe the random variables influencing the input data. This brittleness has several names, including generalization, dataset-shift, data drift, data shift, and concept shift.

We find, perhaps unsurprisingly, that there is no dataset-shift (generalization) problem for simple modulation-recognition problems if the input is a principled extracted data feature rather than I/Q samples. The principled feature here is a matrix of cyclic-cumulant magnitudes of various orders (such as the features depicted in the CSP Blog banner). By principled I simply mean that the feature is directly related to the fundamental mathematical characterization of the data, which is the set of all joint probability density functions for the samples. Such features contrast with data-mining features obtained by rooting around in some giant dataset looking for correlations (and you’ll always find some, principles be damned).

The obtained excellent generalization of our networks when using cyclic-cumulant inputs can be explained by realizing that the (properly estimated and normalized) cyclic cumulants for a BPSK signal with rate , carrier offset of $f_1$, and square-root raised-cosine pulse rolloff of

are exactly the same as those for a BPSK signal with rate

, offset

and rolloff

. All BPSK signals (with a fixed rolloff) are characterized by the same feature matrix. So the distribution of the bit rates and/or the carrier offsets is immaterial. This is not the case for I/Q input data.

The drawback of the cyclic-cumulant-input approach to training neural networks is that, well, you have to estimate, blindly, the cyclic-cumulant matrix. If only we could stick with I/Q inputs and get both the high performance and the excellent generalization that comes with using cyclic cumulants as inputs… Well, we can. We’ve done some work to show that and have a couple MILCOM papers in submission. I’m looking forward to seeing you all again at MILCOM 2023 if we can get those papers accepted.

The crucial point, which I’ve made before and so am in danger of belaboring it, is that to obtain simultaneous good performance and good generalization in machine-learning modulation recognition, one needs a machine that is designed with the modulation-recognition problem in mind. Therefore, we have explicitly rejected the wholesale copying of successful image-recognition neural networks to the RF domain in favor of designing network layers that have the chance to extract the very features that we know work best. The modulation-recognition problem is not the same, in terms of the probabilistic description of the input data, as the image-recognition problem and convolutions won’t cut it. The original motivation for including all the different two-dimensional convolutions in the network was to mimic known good performance of biological image-recognition systems (human eye-brain system). That system is terrible at modulation recognition by staring at plots of I/Q data, but great at finding the cat in the photo.

There is no universal classifier that provides good performance AND good generalization across multiple disparate domains.

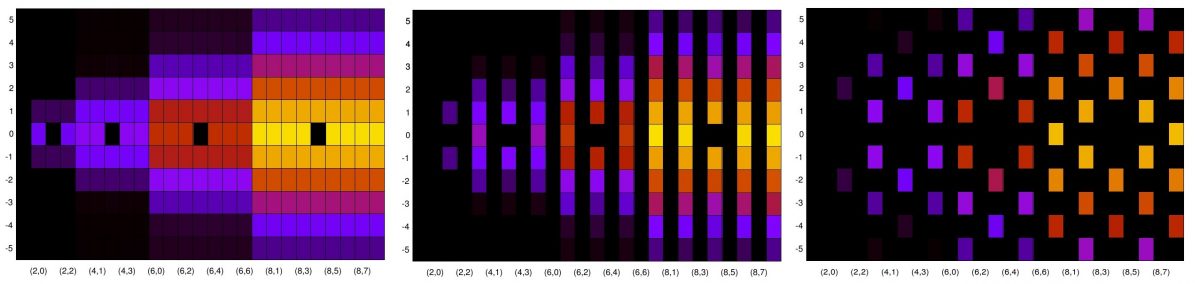

Here is an extracted figure from the paper to motivate you to go read the whole thing. We used the CSP Blog datasets CSPB.ML.2018 and CSPB.ML.2022 to assess performance and generalization differences between networks with different kinds of inputs.

Hi Chad, been loving your work. For a gem of a blog post (though a bit advertising-ish of course) from Renesas that I think is saying the same message, check out https://www.renesas.com/tw/en/blogs/ffts-and-stupid-deep-learning-tricks

Hey Marty! Thanks much for the link and note. Comments like this are great because they strengthen the ties between useful websites. Sometimes it is hard to find information that you can relate to and trust–you’re making things even better!

I do think that Stuart Feffer’s remarks at that link are consistent with my views on the topics of feature engineering, machine learning, and signal processing. Overall, he does support the idea that maybe just throwing the data at the network isn’t the best idea every time.

His example of the Fourier transform in the context of fault diagnosis for rotating machinery is interesting and relevant to the CSP Blog in a couple ways.

First, I myself wondered about whether a machine could learn the Fourier transform. I conclude “not really, no, but kind of, approximately, yes.” More generally, I believe the research program that I’m working on with ODU (John Snoap) is consistent with the idea that you probably should feed the network principled features based on the physics or mathematical structure of the problem at hand–there is no practical universal classifier. You still need some expertise.

But also, secondly, there is a large body of research devoted to using spectral correlation to do early fault diagnosis for rotating machinery, rather than the Fourier transform directly. That is what animates J. Antoni et al. Unfortunately, the data I have from some of those researchers cannot be shared on the CSP Blog yet.

* * *

Feffer says this:

But I’m not so sure. That is, I’m not sure “enough” is achievable in the real world. Nobody has been able to show me they can obtain a DNN for modulation recognition that has both high performance and high generalization when IQ data is at the input. Maybe we don’t have enough time left to do it before the sun goes nova. I suppose I am stuck, then, on what Feffer means, exactly, by “reasonable” here.

Here is where we really really agree:

Hi Chad, first of all thank you for this excellent blog on CSP! It is a great resource I got aware of just recently, and I really appreciate the time and effort you put into it!

Specifically on the above paper, the results are very interesting and confirm some of my own experiments. One question I have is the following: I expected the classification performance to degrade with lower SNR values, but it seems to be fairly independent of SNR, at least over the range covered by your data sets.

What do you think in general about DNN performance vs. SNR? It seems there is a different limitation in the DNN performance, and even at low SNR values, this performance limit can still be reached. Did you ever try even lower SNR to see when DNN performance breaks?

Thanks much,

Peter

Welcome to the CSP Blog Pete! Thanks for the thoughtful comment.

My intuition is that a well-designed well-trained network could have better performance at lower SNRs than a well-designed SP/CSP algorithm. The latter may arise from some optimization problem, but inevitably the core mathematical operations have to be surrounded by engineered subalgorithms. If (and this is a big if) the network can extract high-quality features like cyclic cumulants, spectral correlation, spectral coherence, etc., then it seems intuitive to me that it might very well be able to use those features in better ways, for classification, than human-made approaches such as minimum-distance.

I have not tried to see where performance breaks down as a function of SNR. The reason is that I feel the overall ML approach out there in the world is flawed for moderate and high SNRs. So we need to take that on first, IMO. And I’ve tried, along with Snoap and others. We’ve made some progress.

One recurring theme in RFML, RFSP, and CSP is that people want to say things like: “X algorithmic approach to RF problem Y works as long as the SNR is above Z dB.” But in CSP, performance is a function of the processed block length, so there is no definitive global SNR (or SINR) statement. More accurately, performance is a function of the number of observed instances of the involved random variables (e.g., symbols in a digital signal, carrier periods in a signal with a non-zero CFO, number of hops, number of chips in DSSS, etc.).

Now for typical trained networks with I/Q data at the input, it doesn’t seem like input-data length matters much. But it does for the novel-layers approach of this post. Because the sharpness (local SNR) of the generated tones depends on the block length at the input (this is a CSP-ish ML approach).

Thanks Chad for your reply! My intuition about the primary application of AI-based methods matches yours (low effective SNR regime). I think that the medium-high SNR range can be handled well by non-AI signal processing, that’s why I am specifically looking into low-SNR cases for AI experiments.

I agree the data length aspect is crucial, performance will depend on per-symbol SNR and the number of observations. The term “processing gain” comes to mind here. In my opinion, data length also deserves specific attention in the AI context, since most DNN architectures have fixed input layer dimensions. Hence, it is desirable to derive fixed-size DNN input features from variable-length raw IQ data.

I admit I haven’t gone through all of the equations in your paper in detail yet, but I think the paper shows suitable metrics (or features) for this purpose.

See also My Papers [52] and [54], where we train neural networks using cyclic-cumulant matrix inputs. The cyclic cumulants are blindly estimated from the IQ data, and their matrix dimension does not change with increasing block length. But the quality of the cyclic-cumulant matrix entries does get better with increasing block length. So the network is happy, having fixed-dimension input, and we are happy because we still get the increasing performance benefit of increasing block length.

Unfortunately, extracting the cyclic cumulants requires mathematical and programming [domain] expertise and is costly compared to just shoveling IQ data into the network.

Hi Doctor Spooner, a bit of a two-part theoretical question for you.

So first, I have been doing a lot of reading on deep learning and convolutional neural network solutions for signal classification, identification, detection, etc. I think that your observation of the lack of generalization inherent in these solutions, especially when they are using I/Q data is perhaps the most glaring flaw from a research perspective (by this I mean ignoring the huge amounts of data required for training, the massive amount of energy used to train these systems, etc. and just focusing on issues with the proposed use cases). My only concern (and the first part of this question) is this: will it be enough to cause a shift in research?

I think that in many of these ML-based approaches, the kind of “deliverable” to prove that they function as intended is a nice and tidy confusion matrix which I’ll admit, and I think you can too, many of these solutions do have. Now, I very much agree with what I understand your stance to be which is that these confusion matrices don’t actually tell a whole lot about how extensible the solution is. Sure, it is useful in this specific experimental environment, but how well can it behave outside of it? This is when the brittleness of these solutions could show face, however in a research environment, these problems aren’t always the most obviously dangerous.

My thinking is that while your papers with Doctor Snoap expose a large problem with the I/Q systems, much of the reaction might just be that your methodology simply provides some improvement in a different area. Which it does do that, but perhaps won’t necessarily dissuade from continuing the current brittle research. This brings me to the second part of this question which is a thought on better drawing attention to this flaw.

I’ve also been going through your datasets and their relevant confusion matrices with MSSA and considering the confusion matrices of the ML-based systems alongside it. One thing many of the ML systems have a problem with is stating a signal to be unknown (if they can choose it at all). As such, when they are confused, they tend to be confused in very specific directions (guessing similar but non-identical signals, similar to MSSA) since they have to guess something rather than nothing. The second part of my question: would it be possible to then generate a dataset of signals that aren’t random, but malicious? This would be a dataset intended to confuse systems as much as possible, once again as a kind of compare/contrast to observe the benefits of generalization but also perhaps to show that some of these systems may be taken advantage of (especially those already being used in more cybersecurity oriented spaces). Would be curious to hear your thoughts!

Time will tell, I suppose.

Why is generalization a “different area” than ML system performance? The concerted effort to look away from the serious generalization problem (which is a problem for all supervised-learning ML systems, not just neural networks for modulation recognition) is similar to other concerted efforts to look away from brittleness that we saw in the pre-ML era of signal processing. This is just the new way to avoid a complete assessment of your developed algorithm/system in favor of focusing on what appear to be good results.

The MSSA, and many ML systems, produces incorrect decisions that are “similar to” the true class decision because some subsets of distinct signals have probability structures that are highly similar. If you think of digital QAM, keeping the pulse-shaping function, carrier offset, symbol-clock phase, symbol rate, and probabilistic structure of the symbol sequence constant (e.g., they are IID), the difference is in the probability mass functions of the symbol random variable–the constellation.

You can assess the “distance” between probability density or probability mass functions using things like the KL divergence. You will see that the probability mass functions for 64QAM and 256QAM are much closer (smaller “distance”) than QPSK and 64QAM.

People definitely do this: adversarial attacks on ML systems. There are published papers on this, and I’ve worked with researchers on unpublished efforts as well. As with image recognition, a small, well-crafted additive signal can cause a trained neural network to make very poor decisions indeed. But a small additive signal will not make much difference at all to the time averages needed to extract fundamental probabilistic features from data, such as spectral correlation, spectral coherence, and of course cyclic cumulants. So these studies strike me as goose chases. “We created a very brittle and inexplicable recognizer, then found out that it is brittle indeed. However can we fix it??? Let’s study it more to find a bandaid.” The way to fix it is to not force the machine to learn tiny little things on its way to minimizing the error on the training dataset. Because if you do that, tiny little perturbations will then ruin those tiny little learned things. If you can force a machine to learn what we already know are highly valuable and robust features, then your adversarial-attack problem AND your brittleness (lack of generalization) problems go away.

To find papers about adversarial attacks on mod-rec ML systems, do this Google search:

“adversarial attacks on ml-based modulation recognition”

Thank you for the response! I suppose it is an issue of viewpoint that I was considering generalization to be a different area of performance. I would agree that ignoring it is improper for a complete assessment, I think I may have just been spending too much time in a bubble without it that I wasn’t even considering the conceptual similarities of the systems.

I have spent some time looking into adversarial attacks on image recognition ML systems which is part of what prompted my question. I guess I just hadn’t come across any of the studies on the mod-rec equivalent, so I appreciate the query prompt, thanks!